Alice Fall & Rainer Turim

̶I̶̶̶n̶̶̶ ̶̶̶c̶̶̶o̶̶̶n̶̶̶v̶̶̶e̶̶̶r̶̶̶s̶̶̶a̶̶̶t̶̶̶i̶̶̶o̶̶̶n̶̶̶

✦

Transcribed 10/1/2022

![]()

̶I̶̶̶n̶̶̶ ̶̶̶c̶̶̶o̶̶̶n̶̶̶v̶̶̶e̶̶̶r̶̶̶s̶̶̶a̶̶̶t̶̶̶i̶̶̶o̶̶̶n̶̶̶

✦

Transcribed 10/1/2022

AF

AF: We graduated. I don’t know about you but I’m really missing the structure of critiques and being in our bubble of a community, always within reach of a friend or a professor. I feel like I’m in an echo chamber, making work and then filing it away. Something that I've been thinking about a lot since leaving school is imposter syndrome. How are you feeling about the process of making art without the feedback and discussion that comes with being in that community?

RT: Maybe this is totally naïve, but my ideal mindset right now is making work and sharing it with people who appreciate the way I see. I’m not thinking too much about it becoming anything larger than that. I’m only thinking about the immediate act.

RT

AF: Being outside of that community has definitely allowed me to tune into myself more. I’ve been sharing work recently when I think something’s exciting, not because other people might. Who cares? Still, it’s hard to move away from having feedback all the time. I was talking with some students I was teaching over this past summer about an assignment where students are asked to make a painting, dedicate a lot of time and energy to it, and then destroy it. And that’s it– it’s trust based, you’re just doing it for yourself. I would be uncomfortable creating something, working really hard, and then destroying it. Anything I do I want a record of, even if it’s just for me. I’m trying to pull away from being so output-oriented.

RT: I want to be vulnerable in sharing work, and I think there’s a distinction between vulnerability and insecurity. I was walking up 1st Avenue and I ran into the parent of a friend. He's an artist, a musician, and he said to me I love the pictures you’ve been sharing. I said wow, thank you. That felt so nice. It didn’t feel meaningless. I felt like I was vulnerable sharing work, and then it really resonated with someone enough that they brought it up in person. It feels so much better than artificial praise. I just felt like he got me. I don’t know about you, but sometimes it just hits when someone gets your work. When what they’re saying feels honest. When it doesn’t feel forced.

AF: That is vulnerability. When I share a part of myself with the world and then make a connection with someone in return it feels like we’re saying we see each other, and we appreciate each other because when we look at this work and enter into its space we both feel something, even if those things are different. I love that. I think we all crave that.

RT: What you’re saying reminds me of something you mentioned the other day. You were talking about images reflecting a sense of self back to you. And how you’re engaging with people in Oklahoma who are so afraid of seeing themselves. And how you’ve been thinking about hiding oneself and fear of being vulnerable and how that manifests in your work recently.

AF

AF: Leaving for school and then returning back home has been really clarifying, in a lot of unexpected ways. My feelings are getting much more intensified. I’m immersed in ways of existing here that are at odds with those of the community I was a part of at school. There are so many rules, both explicit and implied, and I feel myself bending to follow them. I guess I’m talking about being myself fully, feeling safe and comfortable with queerness, figuring out how to navigate a sense of self that is filtered by the space I’m in. I hate how performative it feels a lot of the time. Many people here lead with fear and hatred, and like you said, would do anything to avoid vulnerability. I feel it, and I think everyone feels it, no matter who you are. It’s hard to be here, but this is home. I’ve spent most of my life here, and my family’s still here. It’s a complicated relationship, and the more time I spend here the more conflicted I feel. In terms of vulnerability, I feel like making work in this space demands it, and that’s especially true when I’m working with my family. I’m wondering what vulnerability looks like to you. I see you as someone who doesn’t shy away from it.

RT

RT: I dont think I’m that notably vulnerable. I think I try to address my emotions as they arise. I’ve learned recently that true vulnerability is taking responsibility for your emotions. And my definition of vulnerability is constantly evolving. It's scary, because looking back I realize that sometimes when I thought I was being vulnerable I was being immature. How would you define vulnerability?

AF: I think for me it takes a different shape in every situation and that makes it difficult to define. Not pretending to be someone who I’m not, listening closely, engaging with the space around me without defensiveness, openness and surrender, loving a lot. Sometimes I feel like I can articulate it more clearly visually rather than linguistically.

AF

RT: How do you articulate it visually?

AF: I try to allow tenderness and intimacy to come through by bringing forth emotions that are extremely personal, and not shying away from something that’s sad or scary. Seeing that vulnerability in other people’s work is how I can feel connected with them.

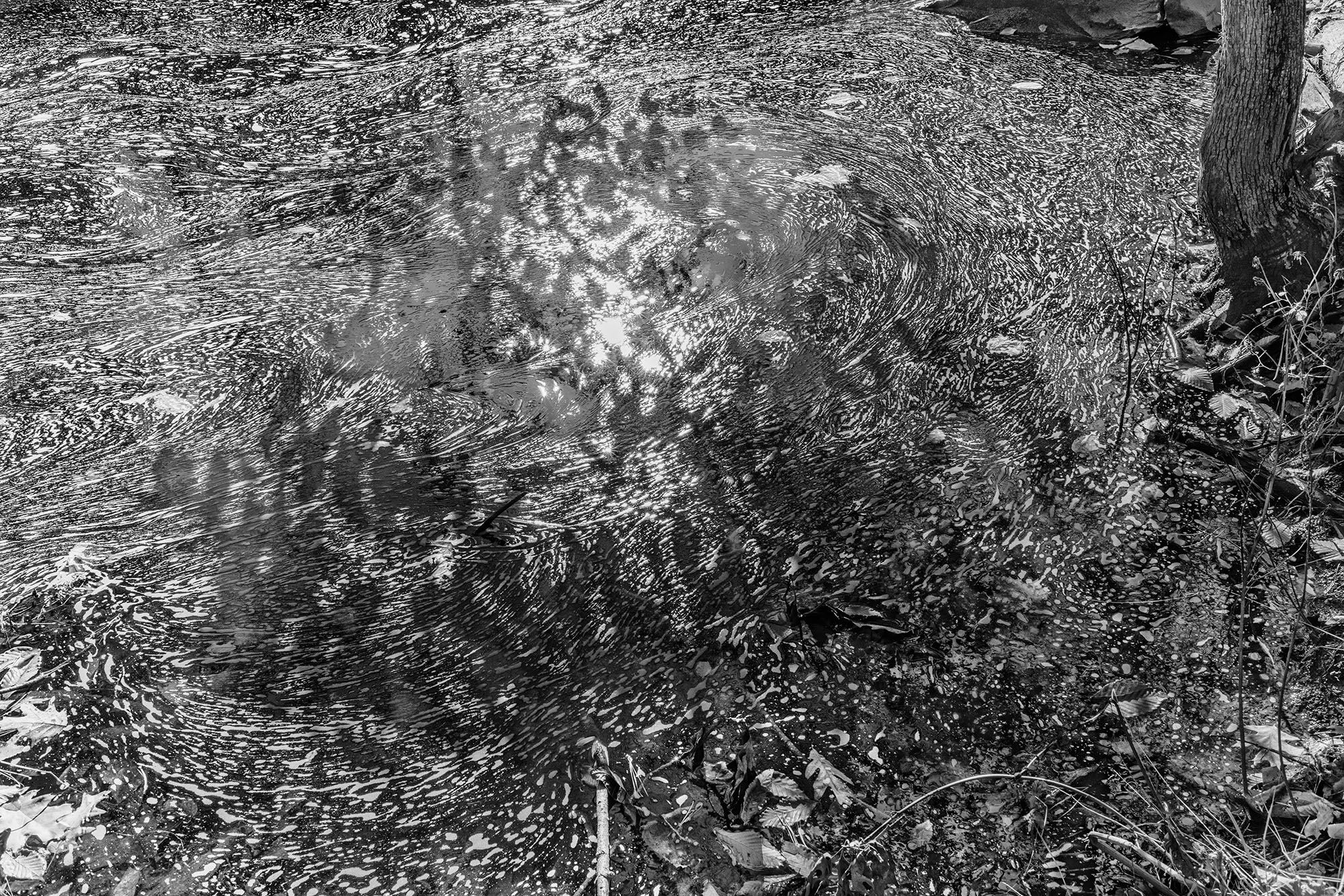

RT: Going forward the way that I want to make pictures is by allowing myself to come through more, or see myself more reflected in the picture. I want to take pictures that reflect my engagement with a person or a place-- allowing myself to fill the frame. I remember having a critique with our friend Maemae, and they started separating my pictures into ones that looked like me putting on the hat of a photographer, and then the ones that felt like me. I didn’t like that at first, because initially the ones I liked more were the ones in the ‘me putting on a hat’ category. Because they felt more visually composed. They were more about scale. In the pictures that Maemae said they saw me in, I was embracing something more vulnerable. I was venturing into more abstract and confusing interpretations of spaces. The others fit more into a historically and traditionally constructed context.

AF: I think I had to learn to photograph like that to be able to not photograph like that. I have to be hyper-aware of what I’m doing in order to step outside of those confines and take off the photographer hat.

RT: Are you doing that?

AF: Sometimes, but I catch myself not doing that a lot of the time too. It’s a hard space to enter into.

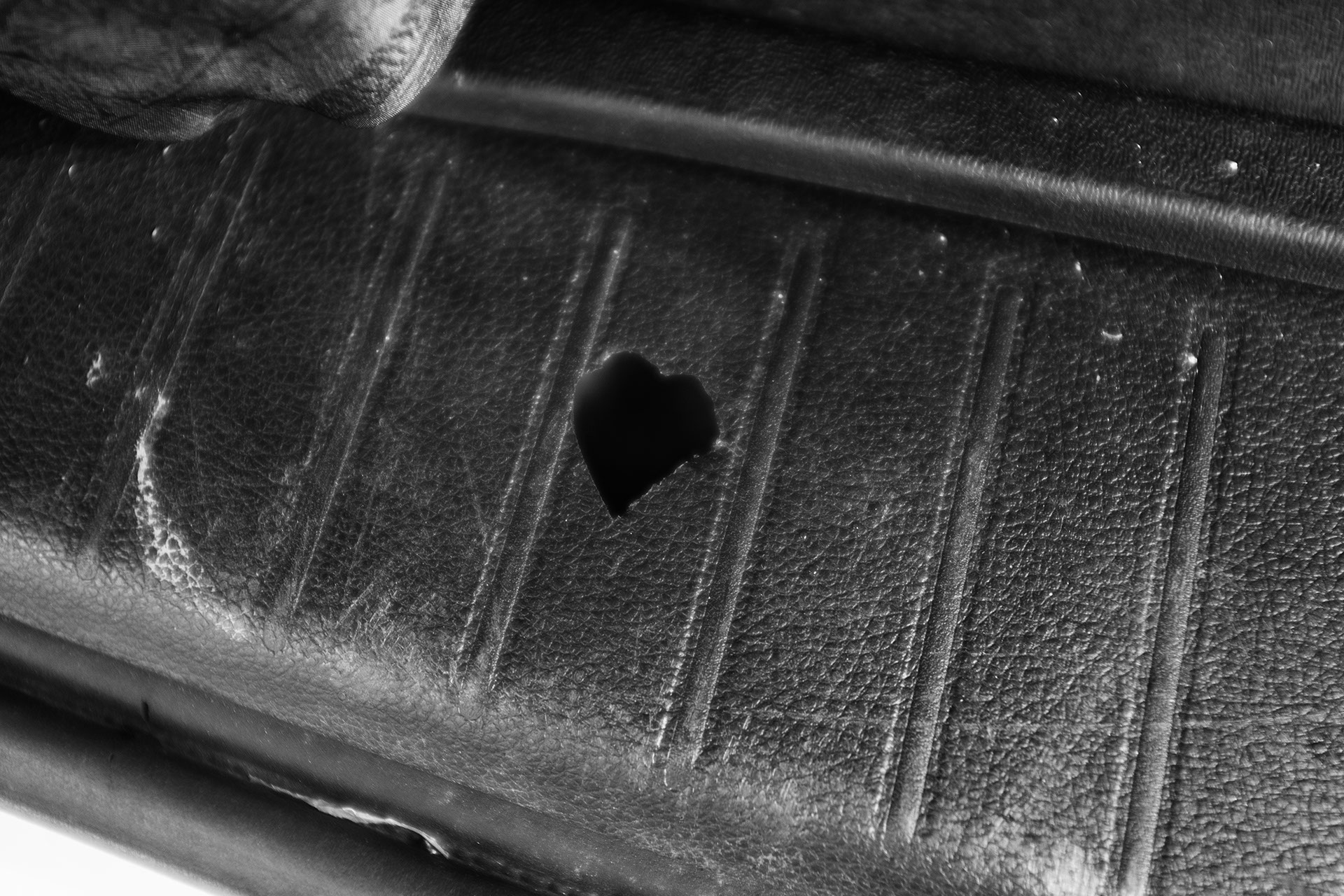

RT: It involves an understanding of who I am. I trust Maemae to tell me who I am, more than someone else. It's interesting because at times I'd rather make pictures that have a confidence to them, as opposed to pictures that aren’t immediately recognizable or absorbable. That’s also a part of vulnerability for me. Taking pictures that aren't instantly going to be loved, or cherished, or automatically accepted as a ‘picture.’ I was in the West Village the other day and I was taking a picture of the corner of this window. I heard this woman say what is he photographing as she walked past. And it was comforting to hear, because it reminded me that people aren’t looking at the same corners I am.

--

--

RT: I went to see this author Hua Hsu in conversation with Lucy Sante. Hua just wrote this memoir, and said it’s really hard when writing about real people in your life to not immediately turn them into superheroes. He spoke to that impulse when we write about someone, to immediately idealize them. I guess my question is how do you go about photographing your family in a way that doesn’t hyper idealize them? How can you avoid turning a character into a superhero?

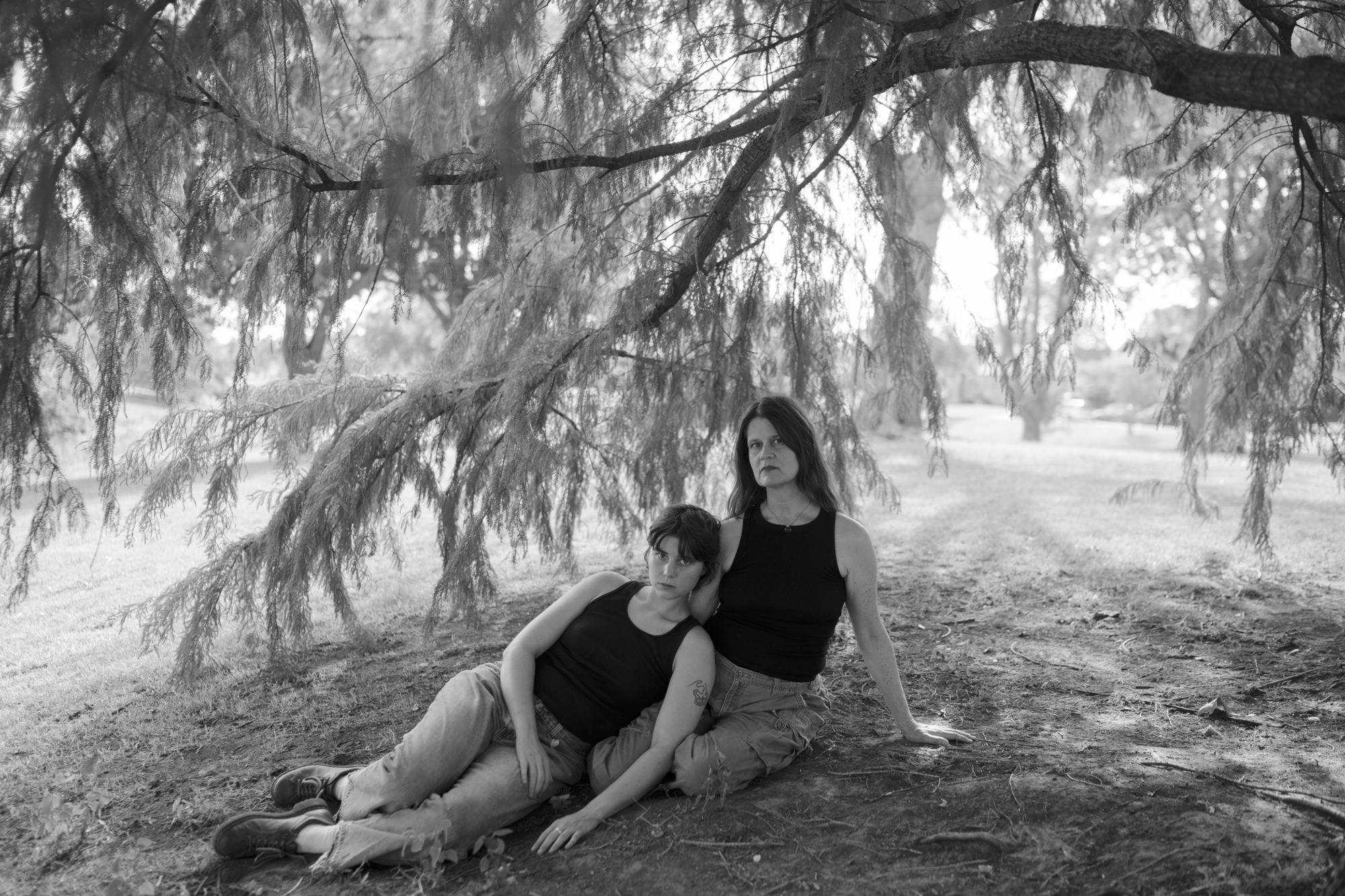

AF: When I'm photographing someone in my family, usually my mom or my sister, I’m seeing them in a way that no viewer ever will understand, not because of a lack of clarity, but because it's hard to move outside of our individual experiences. An image I make is probably going to have entirely different feelings attached to it for me than what you experience when you look at the same image. This is why I usually like looking at work before reading a statement, not the other way around. Everything feels so much richer. What I see is always going to be subjective– it will always rely on my family, my own experience, my own emotions. How do you feel like you see the people you photograph?

RT: I think I try to make ‘happy’ pictures of people. As to create a ‘good’ image of them. Recently I've been more interested in presentability or lack thereof. I’m more interested in reflecting on my true relationships instead of ones that feel more fictionalized or ‘happy go lucky.’

AF: When I’m portraying someone as happy, it’s never so black and white. Nuances will always come through, even if I’m not conscious of them or if they’re untrue to me.

AF

RT: I block the nuance of images sometimes. Sometimes I want to make pictures that speak more to my understanding of people, rather than their idealized understanding of themselves. In Larry Sultan’s Pictures from Home, his father is talking to him about these pictures of his mom, saying your mother doesn’t look good in these, how could you picture your mom like this and Sultan was like these pictures are honest to me, you don’t have to see that in her, you have your own relationship with her, but this is my relationship to her. So sometimes I get caught up on who I make the picture for. And how does the emotional resonance operate differently? What I like about your pictures is that it feels like you’re depicting your family in ways that seem more like a display of a truth. I wouldn’t say a lot of the pictures are portraits, because there is so much motion and movement in them. They can’t fit into the category of ‘portraits.’ I would think of them as operating differently. They display more than just ‘a character’.

AF: Do you think you can feel the relationship that I’m trying to imply and embed in the images?

RT: In the image of your mom with the two lights and her hands on her chest, I can feel your presence because of the flash, but also because the subjectivity is so vivid. The picture exists because you decided this was an important moment. The decision making is so precise. It doesn’t feel like this picture would sit framed on someone’s dresser. I think that’s a special thing. That it wouldn't.

RT: I block the nuance of images sometimes. Sometimes I want to make pictures that speak more to my understanding of people, rather than their idealized understanding of themselves. In Larry Sultan’s Pictures from Home, his father is talking to him about these pictures of his mom, saying your mother doesn’t look good in these, how could you picture your mom like this and Sultan was like these pictures are honest to me, you don’t have to see that in her, you have your own relationship with her, but this is my relationship to her. So sometimes I get caught up on who I make the picture for. And how does the emotional resonance operate differently? What I like about your pictures is that it feels like you’re depicting your family in ways that seem more like a display of a truth. I wouldn’t say a lot of the pictures are portraits, because there is so much motion and movement in them. They can’t fit into the category of ‘portraits.’ I would think of them as operating differently. They display more than just ‘a character’.

AF: Do you think you can feel the relationship that I’m trying to imply and embed in the images?

RT: In the image of your mom with the two lights and her hands on her chest, I can feel your presence because of the flash, but also because the subjectivity is so vivid. The picture exists because you decided this was an important moment. The decision making is so precise. It doesn’t feel like this picture would sit framed on someone’s dresser. I think that’s a special thing. That it wouldn't.

RT: I block the nuance of images sometimes. Sometimes I want to make pictures that speak more to my understanding of people, rather than their idealized understanding of themselves. In Larry Sultan’s Pictures from Home, his father is talking to him about these pictures of his mom, saying your mother doesn’t look good in these, how could you picture your mom like this and Sultan was like these pictures are honest to me, you don’t have to see that in her, you have your own relationship with her, but this is my relationship to her. So sometimes I get caught up on who I make the picture for. And how does the emotional resonance operate differently? What I like about your pictures is that it feels like you’re depicting your family in ways that seem more like a display of a truth. I wouldn’t say a lot of the pictures are portraits, because there is so much motion and movement in them. They can’t fit into the category of ‘portraits.’ I would think of them as operating differently. They display more than just ‘a character’.

AF: Do you think you can feel the relationship that I’m trying to imply and embed in the images?

RT: In the image of your mom with the two lights and her hands on her chest, I can feel your presence because of the flash, but also because the subjectivity is so vivid. The picture exists because you decided this was an important moment. The decision making is so precise. It doesn’t feel like this picture would sit framed on someone’s dresser. I think that’s a special thing. That it wouldn't.

RT: I block the nuance of images sometimes. Sometimes I want to make pictures that speak more to my understanding of people, rather than their idealized understanding of themselves. In Larry Sultan’s Pictures from Home, his father is talking to him about these pictures of his mom, saying your mother doesn’t look good in these, how could you picture your mom like this and Sultan was like these pictures are honest to me, you don’t have to see that in her, you have your own relationship with her, but this is my relationship to her. So sometimes I get caught up on who I make the picture for. And how does the emotional resonance operate differently? What I like about your pictures is that it feels like you’re depicting your family in ways that seem more like a display of a truth. I wouldn’t say a lot of the pictures are portraits, because there is so much motion and movement in them. They can’t fit into the category of ‘portraits.’ I would think of them as operating differently. They display more than just ‘a character’.

AF: Do you think you can feel the relationship that I’m trying to imply and embed in the images?

RT: In the image of your mom with the two lights and her hands on her chest, I can feel your presence because of the flash, but also because the subjectivity is so vivid. The picture exists because you decided this was an important moment. The decision making is so precise. It doesn’t feel like this picture would sit framed on someone’s dresser. I think that’s a special thing. That it wouldn't.

AF: Do you think you can feel the relationship that I’m trying to imply and embed in the images?

RT: In the image of your mom with the two lights and her hands on her chest, I can feel your presence because of the flash, but also because the subjectivity is so vivid. The picture exists because you decided this was an important moment. The decision making is so precise. It doesn’t feel like this picture would sit framed on someone’s dresser. I think that’s a special thing. That it wouldn't.

RT: I block the nuance of images sometimes. Sometimes I want to make pictures that speak more to my understanding of people, rather than their idealized understanding of themselves. In Larry Sultan’s Pictures from Home, his father is talking to him about these pictures of his mom, saying your mother doesn’t look good in these, how could you picture your mom like this and Sultan was like these pictures are honest to me, you don’t have to see that in her, you have your own relationship with her, but this is my relationship to her. So sometimes I get caught up on who I make the picture for. And how does the emotional resonance operate differently? What I like about your pictures is that it feels like you’re depicting your family in ways that seem more like a display of a truth. I wouldn’t say a lot of the pictures are portraits, because there is so much motion and movement in them. They can’t fit into the category of ‘portraits.’ I would think of them as operating differently. They display more than just ‘a character’.

AF: Do you think you can feel the relationship that I’m trying to imply and embed in the images?

RT: In the image of your mom with the two lights and her hands on her chest, I can feel your presence because of the flash, but also because the subjectivity is so vivid. The picture exists because you decided this was an important moment. The decision making is so precise. It doesn’t feel like this picture would sit framed on someone’s dresser. I think that’s a special thing. That it wouldn't.

RT: I block the nuance of images sometimes. Sometimes I want to make pictures that speak more to my understanding of people, rather than their idealized understanding of themselves. In Larry Sultan’s Pictures from Home, his father is talking to him about these pictures of his mom, saying your mother doesn’t look good in these, how could you picture your mom like this and Sultan was like these pictures are honest to me, you don’t have to see that in her, you have your own relationship with her, but this is my relationship to her. So sometimes I get caught up on who I make the picture for. And how does the emotional resonance operate differently? What I like about your pictures is that it feels like you’re depicting your family in ways that seem more like a display of a truth. I wouldn’t say a lot of the pictures are portraits, because there is so much motion and movement in them. They can’t fit into the category of ‘portraits.’ I would think of them as operating differently. They display more than just ‘a character’.

AF: Do you think you can feel the relationship that I’m trying to imply and embed in the images?

RT: In the image of your mom with the two lights and her hands on her chest, I can feel your presence because of the flash, but also because the subjectivity is so vivid. The picture exists because you decided this was an important moment. The decision making is so precise. It doesn’t feel like this picture would sit framed on someone’s dresser. I think that’s a special thing. That it wouldn't.

RT: I block the nuance of images sometimes. Sometimes I want to make pictures that speak more to my understanding of people, rather than their idealized understanding of themselves. In Larry Sultan’s Pictures from Home, his father is talking to him about these pictures of his mom, saying your mother doesn’t look good in these, how could you picture your mom like this and Sultan was like these pictures are honest to me, you don’t have to see that in her, you have your own relationship with her, but this is my relationship to her. So sometimes I get caught up on who I make the picture for. And how does the emotional resonance operate differently? What I like about your pictures is that it feels like you’re depicting your family in ways that seem more like a display of a truth. I wouldn’t say a lot of the pictures are portraits, because there is so much motion and movement in them. They can’t fit into the category of ‘portraits.’ I would think of them as operating differently. They display more than just ‘a character’.

AF: Do you think you can feel the relationship that I’m trying to imply and embed in the images?

RT: In the image of your mom with the two lights and her hands on her chest, I can feel your presence because of the flash, but also because the subjectivity is so vivid. The picture exists because you decided this was an important moment. The decision making is so precise. It doesn’t feel like this picture would sit framed on someone’s dresser. I think that’s a special thing. That it wouldn't.

RT: I block the nuance of images sometimes. Sometimes I want to make pictures that speak more to my understanding of people, rather than their idealized understanding of themselves. In Larry Sultan’s Pictures from Home, his father is talking to him about these pictures of his mom, saying your mother doesn’t look good in these, how could you picture your mom like this and Sultan was like these pictures are honest to me, you don’t have to see that in her, you have your own relationship with her, but this is my relationship to her. So sometimes I get caught up on who I make the picture for. And how does the emotional resonance operate differently? What I like about your pictures is that it feels like you’re depicting your family in ways that seem more like a display of a truth. I wouldn’t say a lot of the pictures are portraits, because there is so much motion and movement in them. They can’t fit into the category of ‘portraits.’ I would think of them as operating differently. They display more than just ‘a character’.

AF: Do you think you can feel the relationship that I’m trying to imply and embed in the images?

RT: In the image of your mom with the two lights and her hands on her chest, I can feel your presence because of the flash, but also because the subjectivity is so vivid. The picture exists because you decided this was an important moment. The decision making is so precise. It doesn’t feel like this picture would sit framed on someone’s dresser. I think that’s a special thing. That it wouldn't.

![]()

AF: Do you think you can feel the relationship that I’m trying to imply and embed in the images?

RT: In the image of your mom with the two lights and her hands on her chest, I can feel your presence because of the flash, but also because the subjectivity is so vivid. The picture exists because you decided this was an important moment. The decision making is so precise. It doesn’t feel like this picture would sit framed on someone’s dresser. I think that’s a special thing. That it wouldn't.

RT

AF: I was listening to this interview with Martin Parr and he was talking about his use of flash, and how inherently the pictures are fictionalized even though he’s not adjusting subjects within the frame. His use of flash is doing something that’s impossible for the human eye to do, and it definitely makes me hyper-aware of his presence in the moment. I thought about that a lot in the context of that image of my mom that you’re talking about, and how the flash really emphasizes my subjectivity. Also, what I think about what you were saying about Larry Sultan defending his perspective when I’m photographing my family is that I’m never going to use an image that someone is genuinely opposed to, but there will always be that range that I’m photographing within where images will reflect a side that is less recognized, or an image will cause someone to think about that person in in a new way. Or people will think there’s an unnecessary layer of drama, or that I’m hyper-fixated and revealing too much of certain qualities. My mom and I made a lot of pictures that night. When we were looking back at the images, she said I feel most like myself in that one you’re referencing. It was a meeting in the middle. That takes a lot of time and trust. It’s easier for me to only consider my perspective.

RT: Do you find yourself making pictures that are truthful and honest to you that the other person is upset with?

AF: Sometimes I want to, but I’ll stop myself before I do it if it’s too personal. I can’t ask to turn it into something that’s mine when it’s something that belongs to them.

![]()

RT: Do you find yourself making pictures that are truthful and honest to you that the other person is upset with?

AF: Sometimes I want to, but I’ll stop myself before I do it if it’s too personal. I can’t ask to turn it into something that’s mine when it’s something that belongs to them.

RT

AF

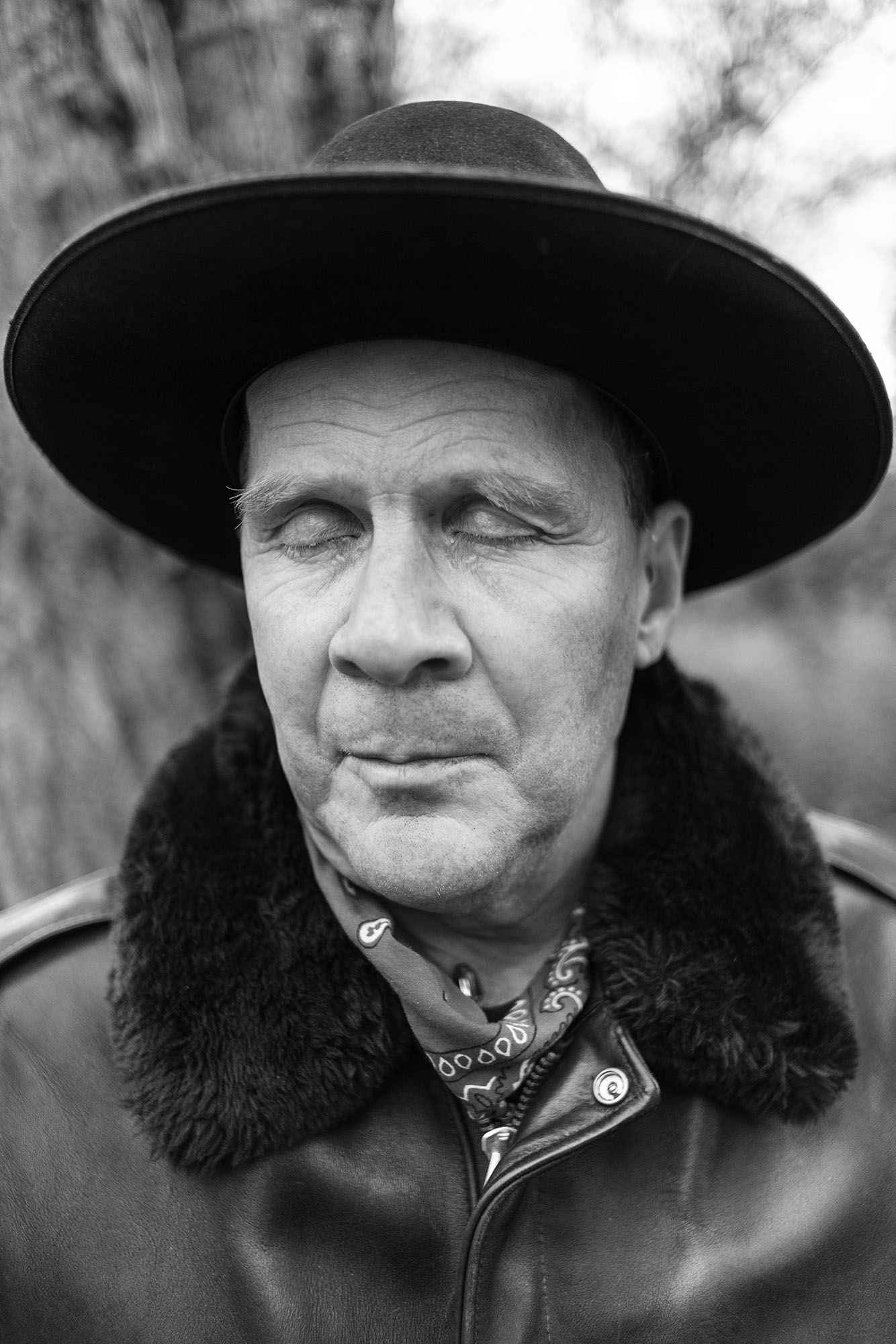

RT: I feel like I am trying to take more pictures that don’t normally exist in my family. Asking my dad to pose in ways that aren’t usual to him. Listening to you say that sometimes moments feel too personal to someone to share with the world makes me think about the conversation I have with my dad in which I’m asking him to pause and look a certain way.

AF: What do you say to him in those moments? If he’s uncomfortable.

RT: That I think this is going to be a beautiful picture. And usually he understands. It’s different having that conversation with him than having it with a stranger on the street.

AF: I’m learning that I don’t think I could ever do that.

RT: And I don’t want to. Sometimes it feels like it tests our relationship.

AF

AF: It’s frustrating to me. I catch myself thinking, we know each other so well, why do I have to explain myself? Or justify why I want to make this image? I get embarrassed. I don’t want to make them uncomfortable. But I see potential in the moment.

RT: I think that sheds light on the boundaries of your relationship with that person. You’ve never asked them to be uncomfortable in this way and in return you are also facing discomfort. But we’re just trying to expand these boundaries of visualization. I think this is difficult, but necessary. It’s exciting to see new sides of people.

RT

RT

AF: It helps me understand something that maybe I don’t yet have the language for. A feeling that I know is coming, but has just begun to grow. Something I’m curious about, but haven’t fully faced before. It makes me think of what Elle Pérez said about that space where something is a photograph and not quite a word. I've been thinking about that in-between space a lot.

RT: I know that the way my family is most often portrayed: eyes open, smiling, in that specifically constructed way. Then there are ways to see that feel new to me. These are questions I was asking myself a lot at college: what does it mean to see my parents asleep? And why isn’t that visualized normally? The pictures feel like actualizations of curious thoughts.

AF: I like what you said about how the posed pictures of them looking at the camera and smiling are the ones that exist in excess. That is one way to see them, but the way that they actually exist is so much more undefinable and complex than what the archive is conveying. That’s what we’re reaching towards. How deep can I get? How much can I show you? How much can I reveal to myself? How much can I hold onto?

RT

AF

RT: It feels like, in the moment, trying to reveal to myself. In terms of understanding what something looks like visualized. Trying to disrupt what images so often look like in my memory archive. Turn things upside down. To make a new memory archive.

AF: Yeah, creating an archive that reflects your truth and your specific experience. That’s not the way that we learn to document, especially in terms of the family archive. I’ve been thinking about my own writing practice a lot, and how I’ll sit down and write when something is happening. Something good or bad or unusual. Out of the ordinary. An extreme emotion. When I look back, I see myself reflected back to me in these very intense moments. That’s not the way that I exist. A lot of the time I’m experiencing very neutral things, and I’ve been trying to write more when I’m just bored or confused, or working through something. Trying to document the full picture of the ways I exist.

RT: There are holes in it. And there are holes in the family archive too. That’s really interesting. I don’t journal when I feel calm, and therefore the journal is an archive that is not continuous, nor is the family curated archive.

AF: I think about someone in the future reading my journals (a nightmare), and thinking that that is true and complete. But mostly that’s me being dramatic, and talking about things that are really affecting me at the moment. It’s not the full picture.

RT: Do you feel like your pictures are full picture?

AF: There will always be holes. I think that’s what irritates me and makes me want to keep working. To make a full picture.

RT: Maybe that's the ultimate vulnerability. Trying to photograph the full picture of oneself.

AF: I often catch myself pulling back before I put something down on the page. Overthinking before I allow something to come forward. And as a result I’m restricting all sides from revealing themselves. And maybe resisting that is vulnerability, being able to present yourself fully and say ok sorry if you don’t like it! That’s a good thing. Here we are, coming full circle back to the beginning.

~

RT: I don’t know if that’s ever accomplishable. To photograph all sides. Whether that’s my relationships or myself. But I feel like there’s a vulnerable, honest way to try. Not reducing yourself to one side. Photographing with the possibility for more.

AF: There will always be more to uncover. Oh, that’s so exciting.

AF: Yeah, creating an archive that reflects your truth and your specific experience. That’s not the way that we learn to document, especially in terms of the family archive. I’ve been thinking about my own writing practice a lot, and how I’ll sit down and write when something is happening. Something good or bad or unusual. Out of the ordinary. An extreme emotion. When I look back, I see myself reflected back to me in these very intense moments. That’s not the way that I exist. A lot of the time I’m experiencing very neutral things, and I’ve been trying to write more when I’m just bored or confused, or working through something. Trying to document the full picture of the ways I exist.

RT: There are holes in it. And there are holes in the family archive too. That’s really interesting. I don’t journal when I feel calm, and therefore the journal is an archive that is not continuous, nor is the family curated archive.

AF: I think about someone in the future reading my journals (a nightmare), and thinking that that is true and complete. But mostly that’s me being dramatic, and talking about things that are really affecting me at the moment. It’s not the full picture.

RT: Do you feel like your pictures are full picture?

AF: There will always be holes. I think that’s what irritates me and makes me want to keep working. To make a full picture.

RT: Maybe that's the ultimate vulnerability. Trying to photograph the full picture of oneself.

AF: I often catch myself pulling back before I put something down on the page. Overthinking before I allow something to come forward. And as a result I’m restricting all sides from revealing themselves. And maybe resisting that is vulnerability, being able to present yourself fully and say ok sorry if you don’t like it! That’s a good thing. Here we are, coming full circle back to the beginning.

~

RT: I don’t know if that’s ever accomplishable. To photograph all sides. Whether that’s my relationships or myself. But I feel like there’s a vulnerable, honest way to try. Not reducing yourself to one side. Photographing with the possibility for more.

AF: There will always be more to uncover. Oh, that’s so exciting.

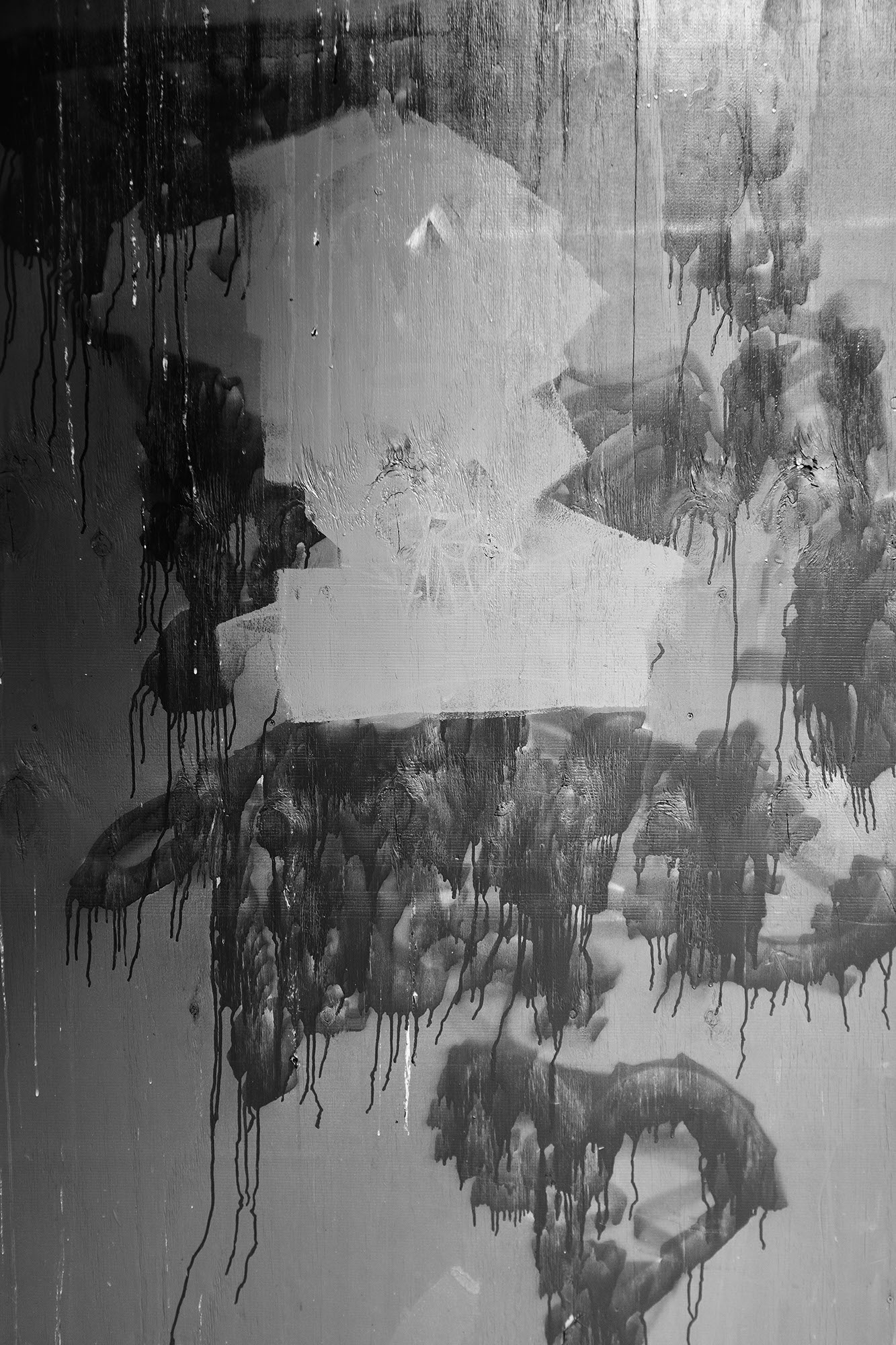

Alice Fall is a photographer from Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. She lives and works between Oklahoma City and New York. In 2022, Fall received her B.A. in Photography at Bard College. As the second place recipient of the 2022 Lenscratch Student Prize for her most recent body of work I Went Back to Sit in the Sun, Fall’s images exist in between spaces– a crease forms between shoulders, limbs curve and drape over each other, and the earth lies dormant for just a moment. The images inhabit a world that is alive and full of movement, fixed in the frame but still unfolding, growing from within. Fall explores intimacy, tenderness, vulnerability, guilt, and queer identity through the fragility, perpetual tension, and transformation of these forces. She works to create spaces of unreality in an effort to crack open possibilities for new ways of seeing, processing, and becoming.

Rainer Turim is a lens-based artist from New York City’s East Village. His visual works aim to understand the nature and language of intimacy, as well as the borders between reality, fantasy, and the memory/dreamscape. In 2019, Turim was the winner of the Ilford US Student Competition.

Turim holds a BA in Photography from Bard College, where he began his ongoing project The Veins I Couldn’t See. In this project he photographs his loved ones and public spaces as indiscernible vestiges of his relationship to the subject and their history. Within this relational reframing, Turim examines the in-between of the past, present, and a possible future through evading any semblance of an entry or exit point.