-

Hyacinth Schukis & Sadie Cook

In conversation

-

⏧ ⏧

⏧

Hyacinth and Sadie met as studio neighbors in a cold colonial barn at the Yale Norfolk residency in the summer of 2019. They have been emailing each other PDF’s since then.

CW: mentions of trauma, sexual assault

S: Hey Hyacinth! I miss you! And your brilliant eBay obsessed art practice.

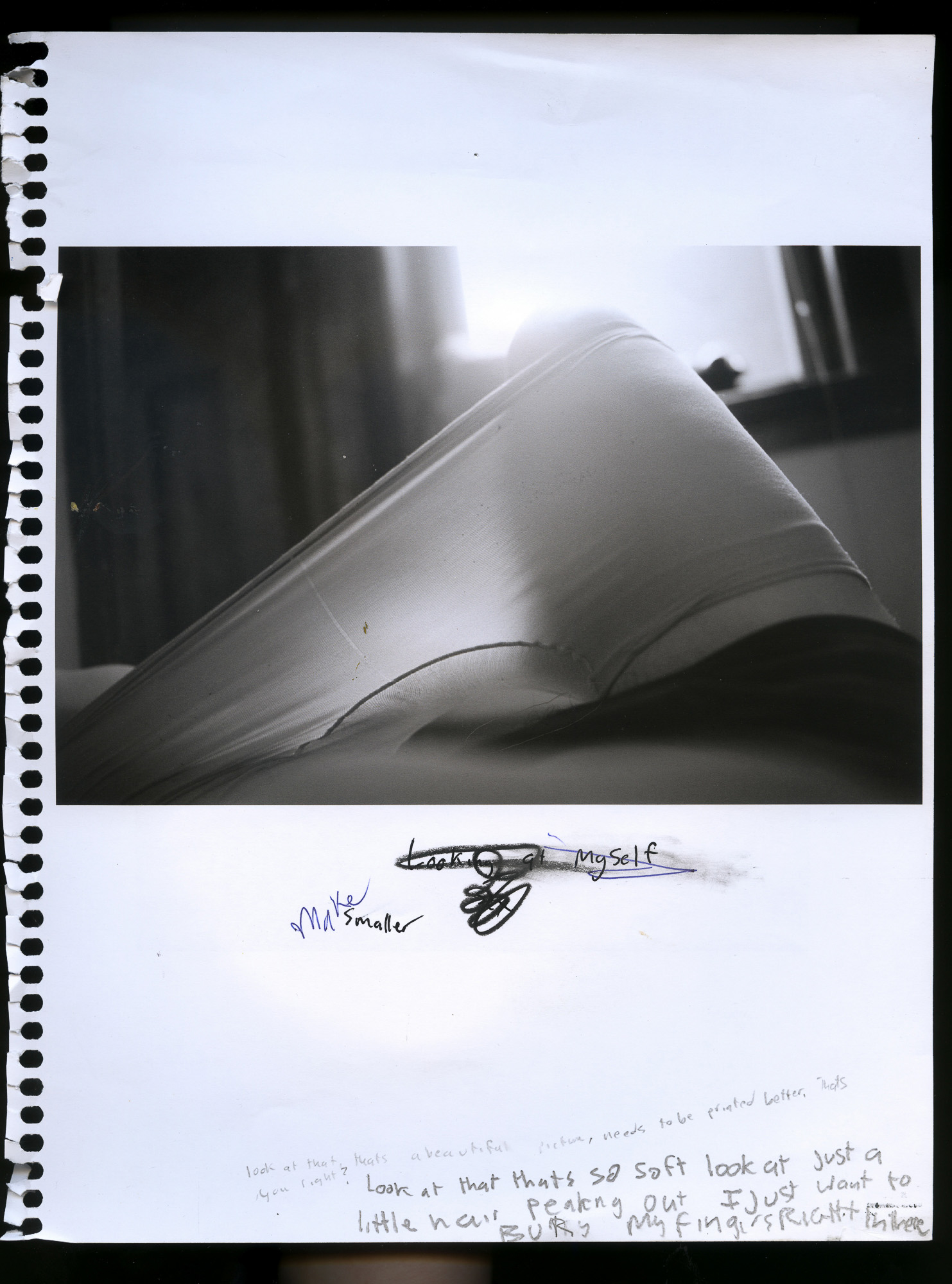

So, I’m remembering our last days in those cold Norfolk studios. My studio was a mess of pictures and bugs and torn things on the floor. Yours was pristine. There were all of these tiny artifacts labeled like pinned butterflies on your walls; your partner’s letters and hair, these tiny ebay souvenirs.

There was this tension between the dry little historical labels next to each item and this feeling the work gave of something so personal; like you were trying to understand your feeling of missing your partner through research and aggregation. We must have talked about this before, but I want to hear from you about research, and personal fantasy. How do they mix together for you?

H: Sadie! I miss you, too, and the stack of glittering work prints you used to carry around, and then throw down wherever they needed to be sorted. You know I very much admire you and your work, so I’m excited to dive in. I always try to invite “mess” into my way of making, but even that often looks and feels like “control.” I am not the type to stain a studio wall light blue or cover the walls in gem appliqué, but I love that about you. For much of undergraduate, I kept a box of lace pins and a level in my bag.

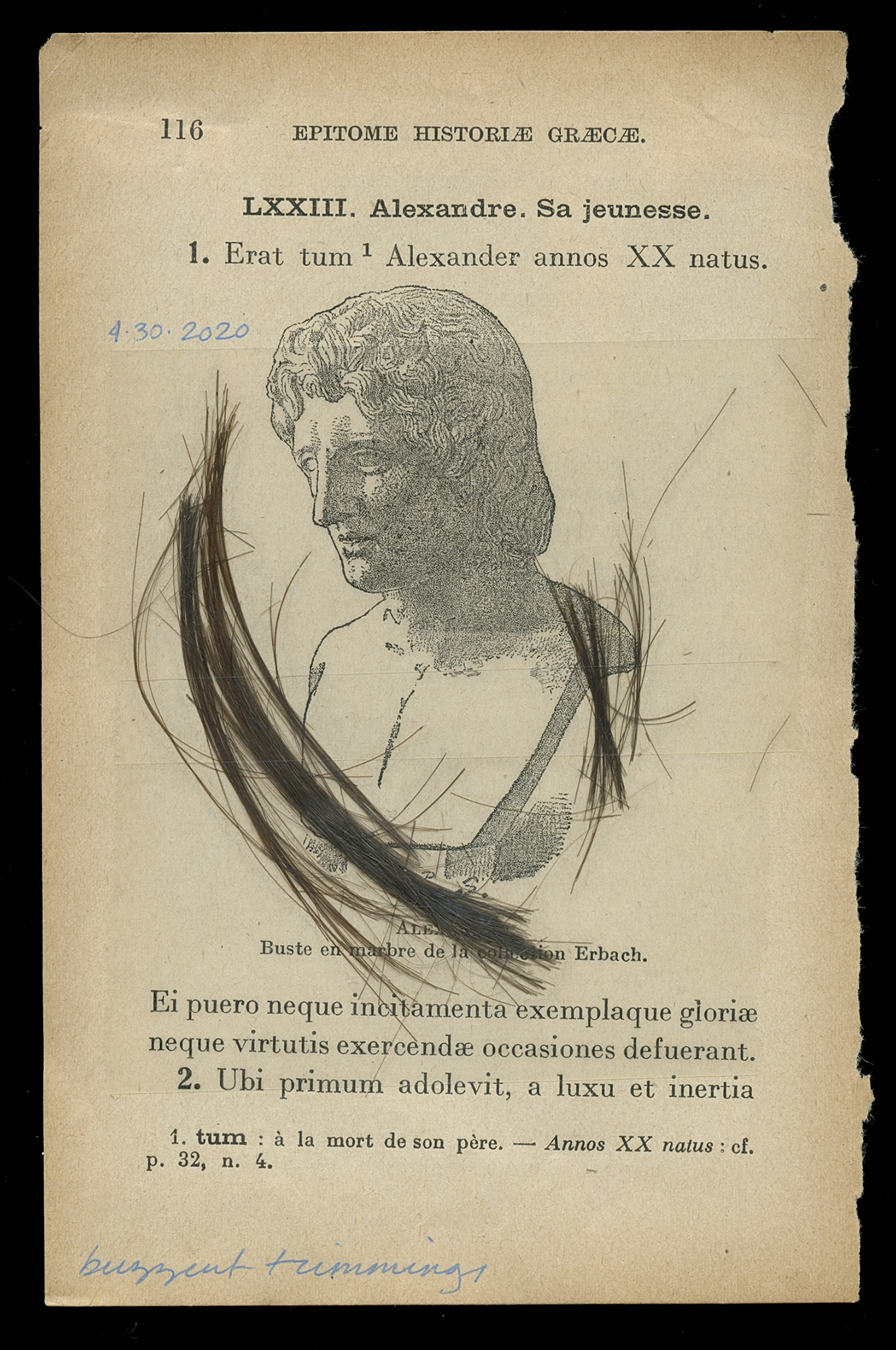

I think in most of my historically minded work there is definitely productive tension between what is researched and what is fantasized. Photography is what allows me to bridge the gap. Bringing the rigor of research (or at least its appearance) into my work is also about fantasy, perhaps the fantasy of having the distance of history to understand myself, trauma, illness, longing, desire, et cetera… it is also about the fantasy and/or conjecture that history is missing some part of what it depicts, and my guesses or hopes for what might be missing. Having briefly considered a career in art history, I’ve found it more rewarding to make pictures that suggest that, than I did writing the history itself (although the choice haunts me). The power of photographs for me has always been their role as physical certifications of something happening, so in this way I can make alternate histories of my body and others’ that are rooted in verifiable objects, which I often relate to the function of holy relics.

Hyacinth Schukis

Sadie Cook

S: You know, your endless restructuring of history is one of the things I love about your work. In my work, I feel like research is separate from my photographs. It’s like scaffolding that shapes my work, but isn’t apparent in the final product. It seems like you use research as an actual building material, which is crazy.

H: I remember when we met we were both making work that placed our self-images within larger systems. Your self-observations and performative acts were literally taped and pinned to the image of the world you operated in.... but I know I am already making assumptions here. I’d like to hear: how, for you, does self portraiture work in the larger universe of your pictures?

S: Self portraiture. Complicated. Sometimes I want to see what I look like. Sometimes I need to hold onto a strong emotion, so that I can look back and understand it. Sometimes, I’m too scared to go photograph other people. Sometimes, I want to make the things I desire feel real--like holding light, or being strong, or flying or swallowing the sky.

A couple years ago, I didn’t see a difference between making self portraits and making any other picture. After all, I’m photographing my world, and I’m a part of my world. Then I started showing people my work, and it often seemed like the self-portraiture aspect overwhelmed the picture itself. Its like people assume that when I show ugly crying or naked pictures of myself, I’m giving permission for to my audience to think/ask whatever they want about my sex life and traumas. I’m not really sure what to do with this intimacy self portraiture opens up. It feels dangerous and vulnerable and powerful, and is something that I’m still trying to figure out.

Okay, but I want to hear about how you think about self portraiture. Do you relate to any of this? For you, I feel like it ties into time and your discomfort with the idea of writing history. Does it? Tell me!

H: I resonate with a lot of what you’re saying! That intimacy wormhole in self portraiture has always frightened and fascinated me, too. I still make “peripheral” and personal work without much of a research dimension and usually end up not wanting to show it, or I take my time in sharing it. I’m not usually a daily self-portraitist, but I also try to keep track of what I look like. I get the most pleasure when images of me and I are in the same room, and viewers refer to the image’s model as “the model”, or someone other than myself. At the end of the day, I’m not entirely sure their linking my self-as-such to the work matters for their experience. I do think this has much to do with my experience of dysphoria, and the fact that I have felt more comfortable signifying things associated with the “feminine” in photographs than I usually do in the world that seems to so badly want to see assigned femininity as my only dimension. There is a certain letting-go I do now before photographing myself in a particular guise when I consider how it might be read.

For a while, when I was younger and beginning to learn to live with PTSD and chronic illness, I had placed the cable release in nearly every shot (even if I wasn’t using it). It was my way of insisting that I must be the master of my visual universe, and the sole writer of my image and body, because at the time I had really lost that sense of myself, and needed it. Now, the language and process of making self portraiture is very important to my work, but the symbolism has mostly fallen out (this isn’t to say I don’t think it’s important). The process of writing with my body over time is instrumental to the process of my work, for me.

When working with other people, I have retained the philosophy that to take a photograph of someone is to open the relation and image to the questions of an often violent ontological history. Photographs for me so often become a “wound” or “proof.” I have rationalized self-portraiture as an effective closing and avoidance of that loop. I think there is still love and joy in photographing other people, and I am trying to open up to that. I have enjoyed the challenge of collaborating with friends and partners to make images, but I am not a photographer of strangers.

In terms of where to go next, an aspect of your work I have always been curious about is the shape of it as an archive, since I know you to be very prolific, and have strong memories of your prints always trailing around you. Is the idea of an archive, personal, or photographic, important to you? Are there photographs you protect or fear damaging? Have you lost photographs?

S: Oh the ARCHIVE, another thing you and I talk about a lot. I don’t see my work as an archive. To me, archive implies something preserved, historical, and categorized for easy access. Your pictures feel like they poke at the idea of a historical archive. But my pictures don’t ever feel organized or removed from me enough to feel like an archive. No one has ever looked at one of my self portraits and talked about “the model” or “the subject.” They always just talk about me.

In my mind, poets are people who carry around leather notebooks and scribble down the words as they go about their day. My hard drive is my version of that notebook. It's this chaotic pool of whatever is important to me on any particular day. When I pull images out of that pile to create a sequence, that's when I feel like I’m making an artwork. It feels wrong to talk about my photographs as an archive, just like it feels wrong to talk about the pile of magazines in art classrooms that elementary schoolers turn into collage as an archive. My pictures feel more like material than works in and of themselves.

I don’t worry about damaging prints. I love that photographs can be both records of the past and physical objects that are dinged up by the present. To me, the ways prints are handled feels more like change than damage. But losing digital pictures is something else entirely. Like, dropping a hard drive makes me so angry and sad. Last time, I felt so sick I threw up. Because it feels like losing memory and language all at once, you know?

Sadie Cook

Hyacinth Schukis

Sadie Cook

H: Poetry… that’s so beautiful to me. I have always admired the surrender your work undergoes. I went to a zoom talk by Eileen Myles a couple months ago where they talked about getting to the stage of their life where the archives were contacting them, and how much anxiety it gave them to see themself that way, see what they had been making that way… I wonder if you fear that as an eventuality, too? I spent some time studying the system of special collections and archives in undergrad. Inspired partially by meeting you, I enjoy making things now that are an archival nightmare-- Scotch tape and packing tape are necessary poisons in my work. ....it still feels like a carefully controlled experiment. In experience, I have found most archives to be inaccessible, (I was studying in them at a time when a mystery illness flared up, and after struggling to make it to the place at the right time, I ended up duplicating a large portion of what I was reviewing on my cell phone to look at where I could better care for my body), but it’s true that my work often masquerades as archives and romanticizes them.

S: I’m so delighted to have drawn you into archival nightmare land.

I literally “hmm”ed out loud when I read your response about photography as an insistence of ownership and mastery of yourself. Ownership is such a complicated word when related to photography and one that makes so much sense when I think about your work. Does this equating of photographing and owning relate to how you think about histories and relics? Is it part of your reluctance to photograph strangers?

H: Ownership, agency, and authorship have been operant keywords for my practice for a long time. Signifying those things to myself has been a healing process. I have been interested in reenactment for a long time as a way to symbolically offer that force, or, lend my body to images that I perceived as lacking that dimension. However, I’ve also long been aware of the limits and catches of applying my particular body to this strategy. I am thinking about “possession,” “being possessed”… That being said, I am far less comfortable with using the same apparatus with other people’s bodies and subjectivities seated before it. Having been photographed without enough information/unwillingly enough times, I can’t fit such a practice into my way of making. I also know that everyone has different photographic boundaries.

I am terribly curious about how you photograph people other than yourself, I mean, I’ve been photographed by you once or twice, but, I want to hear about your thinking. What is caught between you, the camera, the subject? Do you feel like you have to enter a state or cross a threshold to photograph others?

S: I’m not sure how I feel about photographing people. Its hard not to think about photographing as owning. That was one of the things that thrilled me about photography. It seemed so crazy that someone would trust another person enough to give away their image. Like, when I was 19, I lived in this tiny studio apartment, and the walls were covered in photographs of strangers. About half the time, I felt so lucky and powerful and connected to other people, and about the half the time I just felt creepy.

If I’m close to someone, like residency friends, roommates, family, then I photograph in a sort of constant automatic way. It's been a part of every relationship I’ve had. Of course, it always needs to be renegotiated. Like, I’ve photographed my sister since she was twelve. There have been times where we are both comfortable enough that I can photograph her on the toilet, or popping zits, or naked. And there are whole years when she can’t stand to be photographed at all.

Anyway, I don’t feel like I need to enter a state to photograph something. To me, photography still seems like the craziest most beautiful thing in the world. But it’s also kind of my job? Like, I love it, but a lot of times, It feels pointless and grueling, and I need to write things on my daily list like, “ask roommate about photographing them in bathtub” or “Spend 90 minutes taking pictures of pretending to fly” to make sure I get anything done.

I feel like my daily practice is pretty circular and obvious--photograph, research, edit, photograph, research, edit. But I’ve never been totally sure what your process is. It sometimes feels like I’ll wander into your studio every day for a week, and it’ll be practically empty. And then I’ll come in a day later and a fully realized project will be scattered over all the walls. What does your practice look like on a daily level? What are you gonna do today?

H: Today, I’m sitting on my partner’s couch, writing you, reading, and generally decompressing following my end of term review for my MFA program. I envy your consistency... And, you caught me! I don’t really do any one thing every day, except shower, drink 2-4 cups of coffee, and walk my dog (whose consistency I depend on). There are certain parts of my practice that I have turned into bodily appendages that are ready to catch any falling thought, namely my sketchbook, and, more recently, folders where I compile other people’s pictures, but there are others that I will let sit for months, weeks, years at a time before I return to them. For the last few years I have worked in surges, which I can tie to my desire to fabricate each and every component of something, as well as the way being frequently sick while working part time and double majoring in a quarter system affected my work. However, the smattering of images you’ll encounter on my wall is usually a constellation of connected things that has been accreting in my mind for months. I am learning to live with the grooves in my brain for now, but I also have been working to find focus again, er, turn it into my job (but, to roughly quote a meme, I don’t dream of labor).

As your foil, perhaps, these days I almost never have a camera on me. I have to talk myself into it, write it down as an intention. I have had times where I’d carry a 35mm or a Brownie around, often when traveling (which has its problems as a mindset-- i.e. most of my work is made deeply within my “home” or very very far from it). I am much fonder of cameras that are painful/hard to carry around, that make Barthes’ “noise of time.” When I upgraded to full frame, instead of buying a mirrorless camera, I bought a clunky DSLR whose noises excited me. In my current studio situation, I haul my cameras back and forth, which has made it all the more conscious. I think the presence of a camera or the decided absence of all cameras are both methods for accessing the sacred. These days I take a lot of “notes” on my cell phone, and my project recently has been to learn how to use and organize that vast quantity of information. I’ve started working on processing my sketchbook, too.

Sadie Cook

Hyacinth Schukis

S: You know, one day, I want to go camera shopping with you. It would be so funny. I want cameras that are so light and silent and fast that photographing doesn’t feel like an event at all, more like some continuous process of thinking. We would be yanking eachother towards the exact opposite ends of the camera store.

H: Oh, good grief. There are only a few camera stores that could be. I feel like we’ll someday be assigned to trade cameras… Or it feels like an assignment I would receive…

S: Or an assignment you would give.

H: Are there things important to your practice that you don’t do everyday? Events that have changed its course?

S: Finding the right form for a project feels like an event. That moment when the pictures and the form click together comes from months of thought and worry and having no idea what I’m doing. I feel like that moment is for me what photographing is for you.

People are definitely a non daily essential. About once a month, I’ll get so excited about an idea that it's just bursting, and I need someone to honestly tell me if its dumb. Once a week, I’ll get really sad and I’ll need to talk to someone who loves photography so that we can feel excited together. I don’t think I’m as certain about morality as a lot of my friends, so when I get stuck in an ethical spiral, I’ll talk it through with a friend.

Of course, there are also singular things that have changed my whole practice. I started to think about trace and touch in a serious way after dating someone who refused to let me photograph her or put anything online that might be proof of our relationship. I wanted to figure out how to record and understand this relationship. I ended documenting the traces she left on my body, on how I breathed, in my apartment. I’ve got little life trail markers like that that I can point to. Being raped. Trying to understand queerness. Going to Russia.

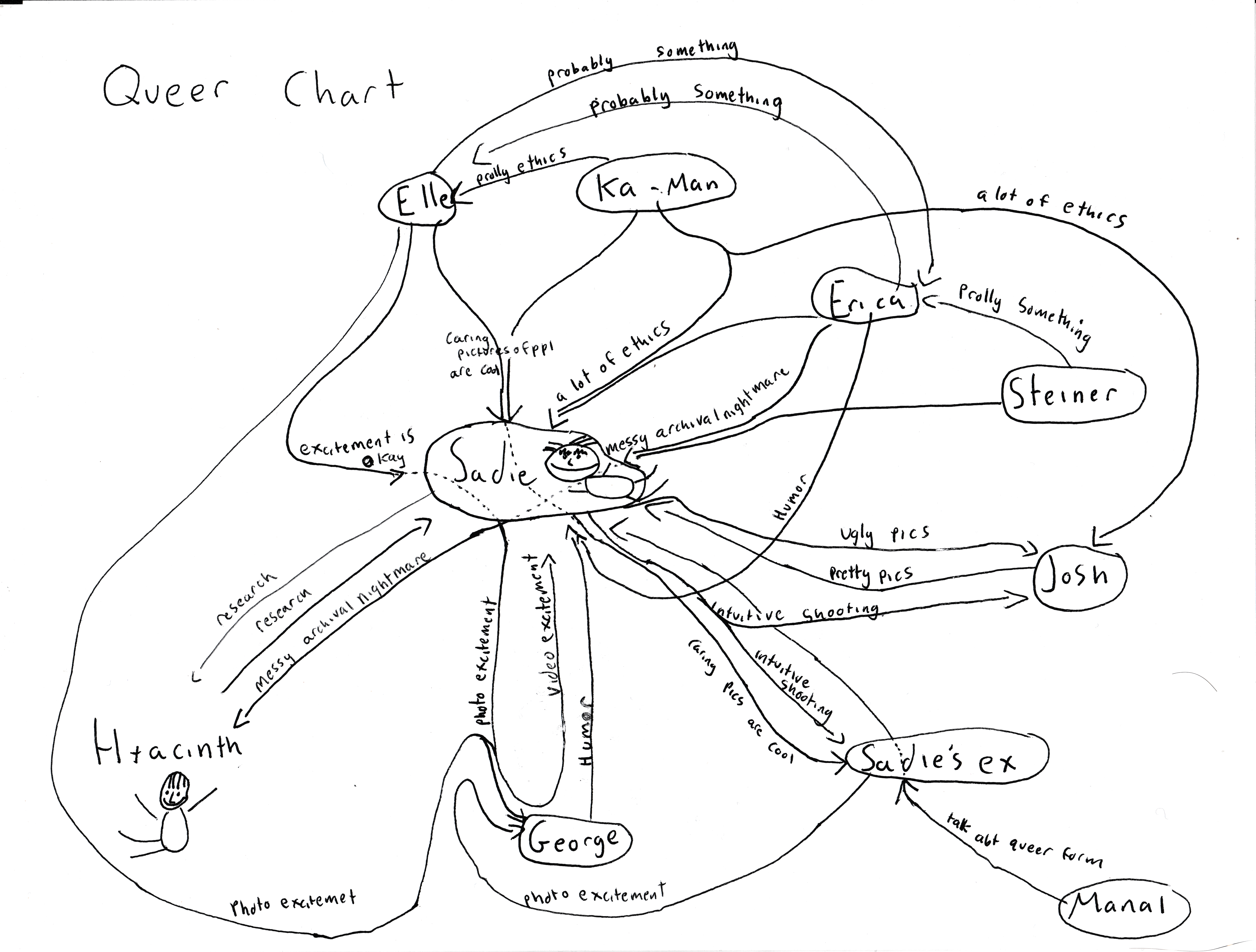

Anyway, now that I’ve said the Q word, I think we should venture into QUEERNESS. To quote something you said in our pre-interview convo: “Where is it? What is it? Why do interviews always out people?”

H: Queerness, yes, let’s talk about it, although I think we have talked about it already. I do feel like interviews can often “out” people, causing them to put up defenses and to have the answers on differencing... It’s exhausting to insist I am “different” or “the same,” honestly. But, I am also excited by the prospect of / conversations about queer photography. If I made a Venn Diagram of queerness and photography, things that fuel me like “longing” and “repurposed objects” would be in the middle. I don’t have a good “what” or “where,” most days. Perhaps the more accurate statement for me is-- I want to talk about queerness but I am hesitant to define it.

How do you want to talk about it?

S: I don’t know. When I talk about my work to queer people, I have this whole speel about the non-archival, the emphasis on touch, the use of traditional photographic style and technique to question and re-own. It feels true. At the same time, I feel so self-conscious. It’s like I’m worried that queer people will call me out for not being queer enough to know what I’m talking about, and straight people will assume that everything I talk about is universally queer.

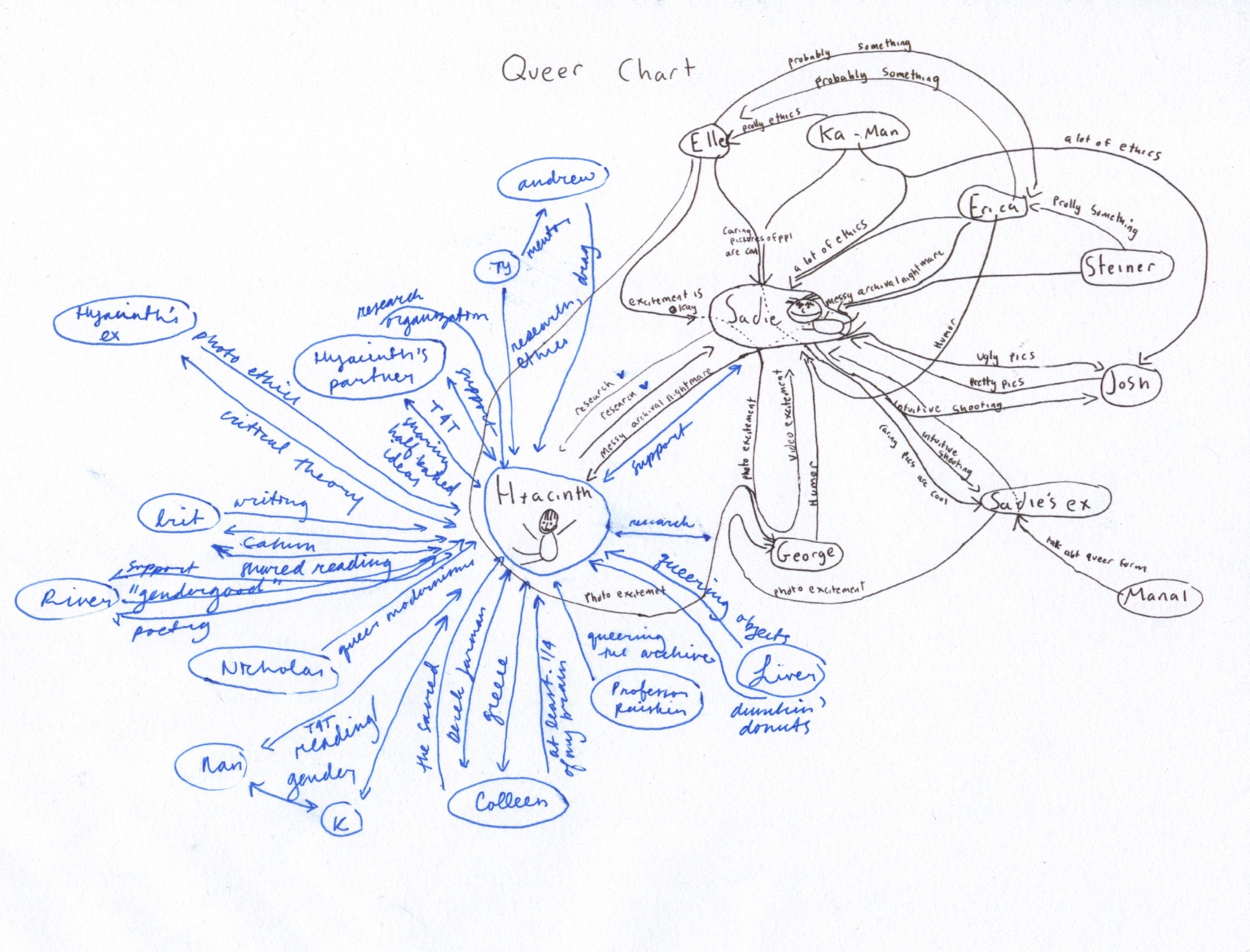

I guess something I can say, I don’t really think about queerness and photography as something that I can make a venn diagram about. I see it more as one of those weird spider web looking things, like a mind map. Let me draw it:

Sadie Cook

It's messy! And weird. And I’m not even sure if any of these traits are queer. Maybe they are just traits of the artists I know who happen to be queer. But also I only know them so well because they are queer. I love thinking about this million people art conversation happening around me, but I don’t really know how to define anything. Maybe we’ll have definitions when we are older.

H: You’re right, I think I fear getting queerness wrong, even though it brings me great joy to see it in my work now, and I did read the Queer Art of Failure once…

Okay, let me add mine:

Hyacinth Schukis

S: I want to keep talking to you forever. But we have a deadline. I guess, we’ve talked so much about fantasy that it seems right to end it there. So, to shamelessly steal a closing question from the amazing Efrem Zelony-Mindell, what do you want, if you could have anything in the world?

H: Anything-- I want to watch the sun rise on the Mediterranean sea again. That, or have the ability to learn languages very fast.

Thank you for the amazing conversation, Sadie! Much love to you.

S: Love you Hyacinth. Let’s talk more soon.

____

Hyacinth Schukis is an artist and academic. They are currently based in Portland, Oregon. Hyacinth holds bachelor’s degrees in Art and Art History from the University of Oregon. They are currently an MFA candidate at Image Text Ithaca.

Sadie Cook received a degree in May. Right now, they live in North Carolina. Soon they are moving to Iceland.

Hyacinth Schukis is an artist and academic. They are currently based in Portland, Oregon. Hyacinth holds bachelor’s degrees in Art and Art History from the University of Oregon. They are currently an MFA candidate at Image Text Ithaca.

Sadie Cook received a degree in May. Right now, they live in North Carolina. Soon they are moving to Iceland.