Jenica Heintzelman

& Magali Duzant̶I̶̶̶n̶̶̶ ̶̶̶c̶̶̶o̶̶̶n̶̶̶v̶̶̶e̶̶̶r̶̶̶s̶̶̶a̶̶̶t̶̶̶i̶̶̶o̶̶̶n̶̶̶

︎

Jenica Heintzelman

M: Could you tell me about the origins of this project? What is this project about?

J: That's gonna be a long answer. I started my project Down a Stream when I was in grad school, at Hartford. I really wanted to do a project about healing or a sort of psychological pilgrimage. I needed to start with physical things so I turned to healing and the body and people doing physical therapy. I made a whole series of people doing stretches and strange motions, but it felt like I was missing something. It wasn’t addressing the darker side that I am interested in, and that I've experienced.

I kept coming back to this incident that happened a few years ago, where I had seen a doctor, a naturopathic/Western medicine doctor in Barcelona. He told me, “Oh, your immune system is so suppressed. There's nothing wrong with your body, but you have unresolved trauma and that’s what’s wrong, that’s why you keep getting sick.”

At that moment, I thought, “What does that mean?” The question stayed with me. “What did this doctor know about me that I don't know, or can't figure it out?” So I thought, “Okay, let's go with this as if it's 100% true. How would I go about trying to heal from trauma?” I started looking into all of these mind body therapies, which is a big field, and some of the practices are more accepted than others. Common ones are hypnotherapy, yoga, and Qi Gong. I started going to different sessions and trying them out for myself. I had really mixed feelings, but most of the time, I would come away feeling like something happened. I didn't know what it was, but something felt different.

I was doing it for myself but also for my project, it was part of the research process. I latched on to a couple different practices that were more physical in nature. I started to think, “this is more what I had in mind about healing”, because there was all this doubt that I wasn't getting across with the previous work.

I kept coming back to this incident that happened a few years ago, where I had seen a doctor, a naturopathic/Western medicine doctor in Barcelona. He told me, “Oh, your immune system is so suppressed. There's nothing wrong with your body, but you have unresolved trauma and that’s what’s wrong, that’s why you keep getting sick.”

At that moment, I thought, “What does that mean?” The question stayed with me. “What did this doctor know about me that I don't know, or can't figure it out?” So I thought, “Okay, let's go with this as if it's 100% true. How would I go about trying to heal from trauma?” I started looking into all of these mind body therapies, which is a big field, and some of the practices are more accepted than others. Common ones are hypnotherapy, yoga, and Qi Gong. I started going to different sessions and trying them out for myself. I had really mixed feelings, but most of the time, I would come away feeling like something happened. I didn't know what it was, but something felt different.

I was doing it for myself but also for my project, it was part of the research process. I latched on to a couple different practices that were more physical in nature. I started to think, “this is more what I had in mind about healing”, because there was all this doubt that I wasn't getting across with the previous work.

Jenica Heintzelman

I went to these classes and took photos if they allowed me, but sometimes with no flash, or sometimes I couldn't move from a certain spot. What I was able to photograph was very limited. It was at this point that I turned to the idea of reenactment with some hesitation at first. I studied documentary film as well as photography in my undergraduate studies. I was holding on to some documentary principles that I wasn't even aware of. This idea of reenactment felt like a big step. I didn’t want to cross that line for so long. But when I did, I got pretty excited about it. I started casting people. I was really involved with the wardrobe choices and colors. The work is very intentional, even though I want it to seem like it's not or I kept it a little removed. I wanted people to question it.

A lot of the people that I worked with were dancers and actors who were familiar with these techniques.They would bring their experience and I would bring my experience and we would meet in the middle. It was a very fluid shooting experience. I started planning a bunch of shoots and was excited about this new, fun way to work, but then the pandemic hit. So I had to put a hard stop to doing shoots with various people.

That's when I started to look into more interior shots. That ended up pushing the work in the right direction. It added a bit of mystery and a bit of darkness.

A lot of the people that I worked with were dancers and actors who were familiar with these techniques.They would bring their experience and I would bring my experience and we would meet in the middle. It was a very fluid shooting experience. I started planning a bunch of shoots and was excited about this new, fun way to work, but then the pandemic hit. So I had to put a hard stop to doing shoots with various people.

That's when I started to look into more interior shots. That ended up pushing the work in the right direction. It added a bit of mystery and a bit of darkness.

M: So you're photographing these actions, but then you also have these images of interior details, still-life-esque imagery. Did stepping back, in a sense, help you build out the world of the project? Because it begins to feel like you're not only witnessing these actions, but you're exploring the space of them.

J: I was really interested in how the bodies were touching each other, or holding or supporting each other. But suddenly, I had to work with what I had around me. I was very fortunate that a friend allowed us to come stay with him in a house in Vermont. I was there for a couple months, at the beginning of the pandemic and had access to these interiors that were reminiscent of the house I grew up in. I had the same green-teal color carpet and a lot of wood paneling. It made me think of how important the domestic space was for this work.

Even though the mind-body therapies happen in an office-like setting, there is so much trauma that comes from the domestic space. It felt like a way to bring these two together. I was interested in making the home feel like a place where you are trapped and you can't get out of. For example, I didn’t show any windows or natural light, I wanted it to feel claustrophobic.

Jenica Heintzelman

M: When did the text appear in the project, or when did the text become an aspect of the work?

J: I always imagined there would be some text in the book. It came about through recording sessions with my hypnotherapist. I also had a psychoanalyst do a dream analysis for me. I took the transcripts of these two different practices and transcribed them, but they weren’t exactly right.

I realized that I was still in documentary mode and that I didn’t need to be faithful to what was actually said. So I made the writing process easier by getting rid of those rules, similar to how I had found more freedom shooting reenactments. I had an idea of what I wanted. I would get into a semi-trance state of mind and read the transcripts and start free-writing. It all happened very quickly, in a couple of sessions. That became really important for the book, because photographs can only show the surfaces of things, but the text added the internal landscape of what was going on in the photos. Not that they illustrate the photos, but mixed together it creates a general feeling of uneasiness.

Jenica Heintzelman

M: Many projects that end up in books are simply photographs in a book, whereas this feels very deliberate and very intentional, whilst also feeling incredibly natural.

I was struck by the fact that the text feels like an incantation, that there is such a sense of movement through the book. I'm wondering about your process of laying the work out and your material choices, such as the vellum. How did you come across that?

J: Thank you. Hmm, sequencing -- it took months. I made dummy books, I had little printouts and would shuffle things around endlessly. I played with some pairings and repetition. There's motifs of hands, lamps and these rugs that, for me, are a kind of Freudian cue. It's not something I think a lot of people will pick up on. I was also looking at the formal similarities, shapes that would echo each other, mirroring actions.

I had a loose narrative in my head. It starts with an image of someone's head being held, staring into the distance. I wanted to get this mood of what it felt like for me to go into hypnosis.

Then there's a close-up image of a pinch. This is something that happened during a session, when we were going over how your brain can control the amount of pain you feel.I wanted to include that early on because it felt like an Alice in Wonderland moment, going down the rabbit hole, falling into a trance state.

I put the vellum in there because I liked this idea of adding layers, especially when working with the idea of trauma. It was a reaction to uncovering trauma and dealing with the subconscious. What is it that we can't see or what's being hidden?

Jenica Heintzelman

M: You're coming at this from a place of mixed feelings. I think that's such an interesting space to make work from - the personal, the uncomfortable, and the skeptical. I'm wondering how that continued throughout the work or if it changed?

J: I had a healthy level of skepticism before I did any of this. At one of my first classes, I had somebody look me straight in the eye and tell me that he could levitate. And I stared back and said, “Of course.”

I had mixed feelings because it brought me back to the religious environment where I grew up and would see people react so strongly, but I never felt anything. For example, I went to a laughter class and a woman started crying because she was overcome with emotion. It had released this blockage for her. Whereas, I only felt uncomfortable and was counting down the minutes to the end of class.

My skepticism stayed pretty strong throughout the process. But I would willingly participate 100%, wanting to believe that the next class is going to be the one that unlocks this trauma, or I'm going to feel amazing. The two that were the most impactful for me were hypnotherapy and restorative contact. When I started going to hypnotherapy, I was having a lot of panic attacks and I was experiencing deep, deep anxiety. After my first session, I came home and slept for about six hours straight in the middle of the day. When I woke up, I felt a weight had been lifted. I was surprised at how different I felt.

Restorative contact was also an interesting experience because I was paired with an older man, and my body tensed up from the beginning. We would go through the sequence and progressively that tension would release. I didn't realize how much my body was holding in, and how uncomfortable I was with my body or with the thought of being touched.

This experience with a stranger really affected me and for weeks I would question myself about it -- “Why did I react like that? Would doing it with this person make me uncomfortable?” That’s part of how I am. I’ve learned to question everything, even my own reactions and thoughts which has its pros and cons.

Jenica Heintzelman

From that whole process, I think I ended up coming away more open-minded. I understand it’s not for everybody, but I felt like it positively affected me. To each their own. It made me reframe that experience, and say, “I didn't get anything from that, but those other people did. And who am I to say that that's not worth something?” Because if you're looking for comfort, or this broad term of healing, that can come in so many different ways.

M: This place of mixed feelings ties into my interest in artists who are making work where they're actively researching in an embodied physical way. In the sense that they are a participant, or doing the physical work of figuring this out, as opposed to being a straight documentarian or director. I admire that process.

J: I discovered a new way of working through the whole process, which took parts of my documentary interests, and then added this new part of directing, to really control what's in the image. Someone recently mentioned to me that control can be a reaction to trauma and they found a thread between that reaction and my process which I had never connected before.

M: Do you see that change? Maybe progressing into future projects? Or do you see this method of working as being specific to this project?

J: I’m interested in doing a similar process with different projects. A lot of my excitement comes from the research phase. When I was going to these random classes, I was slightly terrified, but also interested in meeting people. Getting out of my comfort zone was a big adrenaline high for me. I don’t know exactly what the new iteration will be, but the process of rewriting and the idea of reenactment became a lot more fascinating to me. Before I didn't really understand and appreciate work like this. It can be so much more personal and much more powerful to have to have that control.

M: Do you see that change? Maybe progressing into future projects? Or do you see this method of working as being specific to this project?

J: I’m interested in doing a similar process with different projects. A lot of my excitement comes from the research phase. When I was going to these random classes, I was slightly terrified, but also interested in meeting people. Getting out of my comfort zone was a big adrenaline high for me. I don’t know exactly what the new iteration will be, but the process of rewriting and the idea of reenactment became a lot more fascinating to me. Before I didn't really understand and appreciate work like this. It can be so much more personal and much more powerful to have to have that control.

M: I’ve been wanting to ask about your influences? What were you surrounding yourself with whilst working on this?

J: A major influence has been this book that I've seen popping up everywhere since I've read it called The Body Keeps the Score by Dr. Van der Kolk. It's a thick book, but it is all about trauma and the body's response to trauma. I found this book after I had already started working on the project and I read it as fast as I could. I learned so much about my own experiences.

The intersection of psychology and photography also influenced me. I read a book called The Invention of Hysteria and was really interested in how Charcot used photography to classify different ailments at the Salpetriere asylum in Paris. There was so much theater involved and props and everything that went into that to produce “evidence”. I found that really fascinating.

I was also looking at religious imagery and how Renaissance painters would depict religious scenes of pain and healing, especially the crucifixion and resurrection such as Van der Weyden’s The Descent from the Cross. Looking at these images without the symbolism attached, they started to resemble a form of mind-body therapy.

Music was always in the background. In the past few years I’ve gotten more into ambient and electronic music that would really put me in this mental space that's a bit trancelike which seemed appropriate for the work. So I listened to a lot of this genre--musicians like Matchess, Sarah Davachi, and Julianna Barwick. I felt like I could hyper focus when I was listening to it.

During the editing and writing stages I was reading Ingeborg Bachmann, the Austrian poet and watched the film Safe by Todd Haynes which heightened the conflicts that I was having with the work. It helped to edit out a lot of photographs that felt too obvious.

I’d love to talk more about your work. I noticed some similarities from the images you selected for your book that could have easily been included in my source materials. You are also working with found images. Can you talk about how you selected the images?

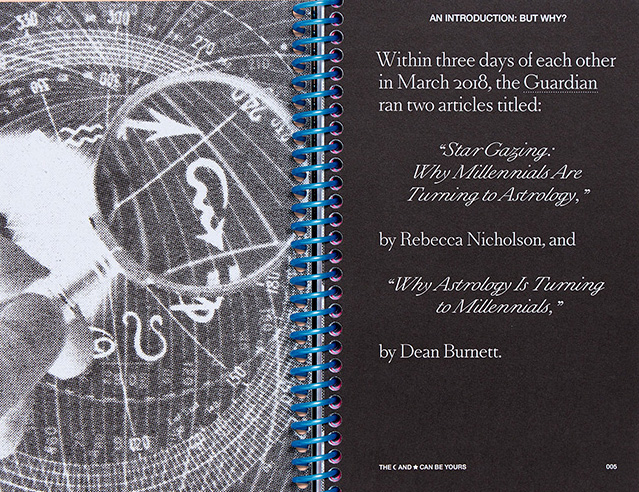

M: I've found that in a lot of my work what I'm most interested in is the actual research process. I'm not as concerned with answering the questions I'm posing, but rather using them as a structure, gathering the information to create a narrative, that is not quite an answer, but some sort of digression or response.

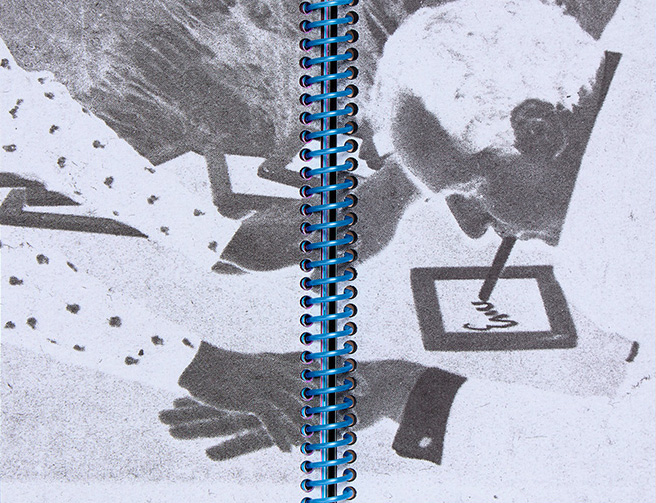

One of the things I had looked into was this idea of sympathetic magic, which has so much to do with touch, and transferring energy or “magic” between objects. I was originally doing these still life photographs where I was photographing my own hands and placing them in still life settings to play with dimension and flatness. To get inspiration, I went to the NYPL Picture Collection and started looking at different subjects of spiritualism such as fortune telling, Tarot, the occult. I found these fantastic images from the 1920s of a team of psychic investigators watching a medium who claimed to be able to produce ectoplasm. I started cropping the photographs to the points of touch or to the points that felt to me to be the most magnetic, that drew one in.

I was looking at psychics and the way that interest in their services or skills is affected by these larger global events. I looked at the New York criminal code to figure out how or why fortune telling is a Class B misdemeanor, but what kept coming back to me was this search for being seen or being understood or for someone to listen to, someone to touch you.

It kept coming up in a lot of my visual research for that project. Hands were such a big thing. They showed up obviously in palm reading, but they also appeared in photographs of seances, people holding hands around a table. This idea of touch was very striking.

One of the things I had looked into was this idea of sympathetic magic, which has so much to do with touch, and transferring energy or “magic” between objects. I was originally doing these still life photographs where I was photographing my own hands and placing them in still life settings to play with dimension and flatness. To get inspiration, I went to the NYPL Picture Collection and started looking at different subjects of spiritualism such as fortune telling, Tarot, the occult. I found these fantastic images from the 1920s of a team of psychic investigators watching a medium who claimed to be able to produce ectoplasm. I started cropping the photographs to the points of touch or to the points that felt to me to be the most magnetic, that drew one in.

I was looking at psychics and the way that interest in their services or skills is affected by these larger global events. I looked at the New York criminal code to figure out how or why fortune telling is a Class B misdemeanor, but what kept coming back to me was this search for being seen or being understood or for someone to listen to, someone to touch you.

It kept coming up in a lot of my visual research for that project. Hands were such a big thing. They showed up obviously in palm reading, but they also appeared in photographs of seances, people holding hands around a table. This idea of touch was very striking.

Magali Duzant

Magali Duzant

J: That's really interesting, because it reminded me of the term transference that is used in therapy, more so in psychoanalysis. When the therapist receives your energy, or trauma or whatever you want to call it--they become vessels to hold it for you. I think this also happens with touch. That was part of my thought process-- how much touch is important in the history of what healing looks like, going back to medieval paintings that depict Christ, and how much is expressed with gestures and touch.

People looking for answers--this used to be filled in the past predominantly by people going to a church, talking to priests, etc. I make a lot of parallels between religious practices and some of these healing modalities. I don't know how I feel about it. It's interesting, but I agree with what you say, it comes down to this human desire to connect with another human on some level, whether that's a therapist, or a psychic or a priest. I think it’s a fundamental thing that we all crave in some form.

M: There are so many versions of creating order out of disorder, or creating an explanation for something larger, so that we are replacing them in these ways in response to how the world is working. People have shifted away from religion, there has been so much change and chaos and the incomprehensibility of wars and even globalism. But then you're shifting to something that is just another way of ordering and another way of being a guide. I think there's a little bit more openness and sort of fluidness to help people look at it but often there's still that unsaid sense of you just want an answer.

J: I have one more question about your use of text. How would you describe it? It's a little diaristic, but with some history. Did you think of the text first when you're working on this?

Magali Duzant

M: My writing style is very much like my speaking style, and it's not for everyone. It was a way of casting myself in the project without necessarily making the project about myself. It's not quite auto fiction, but it is a type of conversational means of

research.

In writing I was trying to identify why I had collected the fliers and images. The text became about the journey of making the work. And then I clicked into this idea of “I am the researcher, the test subject, the narrator.” I used chapters to create structure. So the chapters became the questions I was asking myself while I worked on it, questions of self doubt. It was very much a recording of myself working on a project. I think the questions are probably true for most people, or maybe most artists, “Will I find love? Happiness? Should I continue to make art?”

All of that to say that the writing is anecdotal. So much of it was about me telling a story. I realized that I was writing about my personal experience to connect to the greater subject. So if it's about the Zodiac, through my experience speaking to a woman in a YMCA sauna (who pretty much told me I had it all wrong) - I wanted it to be relatable.

Magali Duzant

J: I loved reading it. It felt very personal. We have a shared interest in really getting ourselves into the research and being part of it. I've always had a thing against self portraits. I don't know if I'll ever cross over that line. But I'm still not there. Maybe that's something I need to question myself on. I used this cast of characters as stand-ins. I filmed myself during sessions, hoping I could make something with that, but it never emerged into anything more than source material.

M: It's funny because I would say I was never someone who was that interested in self portraiture. Maybe that's dealing with my own neuroses or whatever. I found that there's something really fascinating about self portraiture that is one step in one step out. I think there's a really ripe field of working in there because you're both exposing and processing or directing and questioning at the same time, which just feels complex in a way that I like or maybe just kind of sticky and strange. Sticky and strange. We can do a two person show and we'll call it “Sticky and Strange”.

M: It's funny because I would say I was never someone who was that interested in self portraiture. Maybe that's dealing with my own neuroses or whatever. I found that there's something really fascinating about self portraiture that is one step in one step out. I think there's a really ripe field of working in there because you're both exposing and processing or directing and questioning at the same time, which just feels complex in a way that I like or maybe just kind of sticky and strange. Sticky and strange. We can do a two person show and we'll call it “Sticky and Strange”.

J: That pretty much sums it up. I know we could keep going on and on, but this feels like a good place to end. Magali, thank you so much. It was an absolute pleasure talking with you!

Magali Duzant

____

Jenica Heintzelman is a Guatemalan-American photographer born and raised in a suburb of Orlando, Florida. She attended Brigham Young University in Utah where she completed her BFA degree in photography and documentary film in 2010. Jenica received her MFA in photography from the Hartford Art School’s International Limited-Residency program in 2020. During her time there, she was awarded the Presidential Scholarship and the Stanley Fellman Award. Her first book Down a Stream was recently shortlisted for the Fiebre Dummy Award, SELF PUBLISH RIGA 2021 and the ICP/GOST First Book Award. Currently based in Brooklyn, NY her work explores themes of vulnerability, trauma and the notion of healing.

Magali Duzant is an artist and writer based in New York and Zürich. In her approach to artist books, installations, and public commissions, she couples a research-based practice with a poetic and and often humorous knack for capturing our intimate, yet shared, experiences. Her work has been exhibited internationally at the 2021 Singapore Art Week, Queens Museum, NY; UQO Gallery, Canada; Centre for Contemporary Photography, Melbourne, Kunstgewerbemuseum in Dresden, and the 2018 Mardin Biennial in Turkey amongst others. She has published three artist books, I Looked & Looked, Light Blue Desire, and The Moon And Stars Can Be Yours and has completed commissions for Memorial Sloan Kettering, Supercollider, ABC No Rio, and Artists Alliance Inc. Duzant holds an MFA in Photography from Parsons School of Design and a BHA in Fine Arts and Visual Culture from Carnegie Mellon University.