-

Jun Tan & Delaney Holton

In conversation-

⏦ ⏦ ⏦ ⏦ ⏦

⏦ ⏦ ⏦ ⏦

Delaney Holton: How would you describe the “way of looking” that your work manifests? How did you come to your current way of shooting?Jun Tan: In Chinese, one of the words for “photography” is “照相”, whose literal reading means “to reflect the likeness or appearance” of a thing. I’m interested in the relationship between those two subjects: a subject’s literal appearance, and how reflecting or mimicking its appearance—through photography—introduces a sense of tension that the subject itself may not physically possess, and raises questions that speak to more than what the photograph depicts. During the actual process of looking and making pictures, I’m rarely explicitly aware of when this quality is present; I’m triggered to take a photograph by some vague, nagging sense of visual interest, which then gets narrowed down and distilled into a clearer vision through aggressive editing, months or years after the fact. It’s been quite difficult for me to narrow down what I’m looking for into a cohesive practice, especially since I don’t really work in series or projects. Instead, I think a lot about what a teacher of mine once said—that making work, or even just the act of taking a photograph, can be as effortless and subconscious as breathing in and out. I’d like my practice to have that same sort of lightness and spontaneity, like the sense of grounding that one feels after a particularly deep exhale—a recognition of being here, being in the moment, and seeing.

Delaney: Given the background you have in other kinds of photography – photojournalism and formal documentary, as in your book Produce, has it been an explicit decision to work within a more vernacular sensibility?

Jun: Partly choice, mostly necessity. Moving away from family and friends (and the intimate work I was primarily making) to one of the most photographed places in the world forced me to re-evaluate my way of looking and grapple with the natural instinct to make work about the city. I quickly realized: as a twenty-something moving here for work with a shallow engagement with the city and its community, I had nothing to say about New York that hasn't already been said, and it felt disingenuous to try to fit myself within the mold of “photography about New York.” In response to this, I made an active decision to take “place”, or a sense of recognizable “place”, away from the work—the photograph can be taken in New York, Berlin, China, or wherever, but I didn’t want the image’s value to turn on it being a reliable depiction of where it was made. This obviously moves away from some of the louder, more documentary photographs that I had been making earlier, and I find myself wondering whether I will stop making this sort of work. Maybe I don’t have to; the process is a mode of image production not around a specific topic or subject, but on a sense of curiosity, an examination of the world and its surfaces, and a quiet observation of what is built, what is being torn down, and what endures.

Jun Tan

Delaney: It's interesting that you use the term “louder” to describe some of your past work, then “quiet observation” for more recent photographs. Hearing that, I think of differences in how energy is directed — external emanation versus interiority or a reverential tenor. I also think about ambient noise when looking at your pictures. Can you expand on your analogy of sound? Where does the volume of your images come from or what exactly determines its degree and quality?

Jun: Pictures themselves can’t depict sound, physically, but when we look at them we automatically feel some sense of auditory presence regardless of what the photograph is physically showing. And there’s an implicit translation between sound and space; your use of “external emanation versus interiority” illustrates this point exactly, where an image that is “loud” takes up space and defines itself clearly, a “quiet” photograph feels more like the ambiance of a room, a computer fan, the clunk of a radiator as it turns on, reminding you of its presence. And it contributes to how we read the photograph as well—part of my motivation for these quieter images is to try to make photographs that are more difficult to read and resolve, as Teju Cole puts in a recent interview: “images that make people go hmmm” instead of wow, (and there’s the auditory notion again). As to applying this analogy to my own work, I think there’s a big gap between a quiet photograph with nothing to say, and a quiet photograph that hums with energy—99% of pictures that I take fall into the former, and the one percent that I cherish are of the latter, where the image contains something unresolved, or that it has some ability to spur on ideas, memories, and associations beyond what the image can depict. There’s no fixed way to determine what that is like; all that matters is that the photograph may be quiet, but not silent.

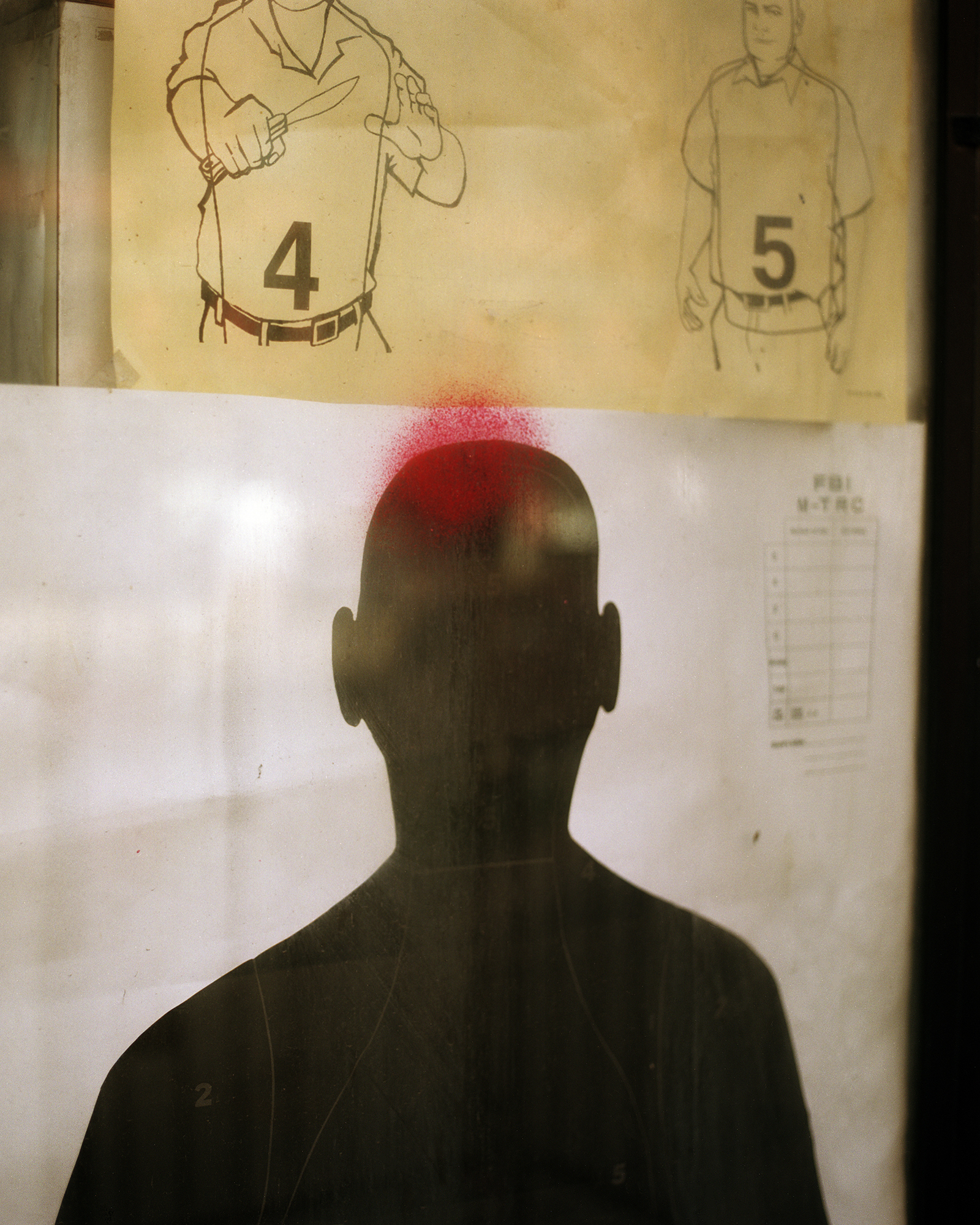

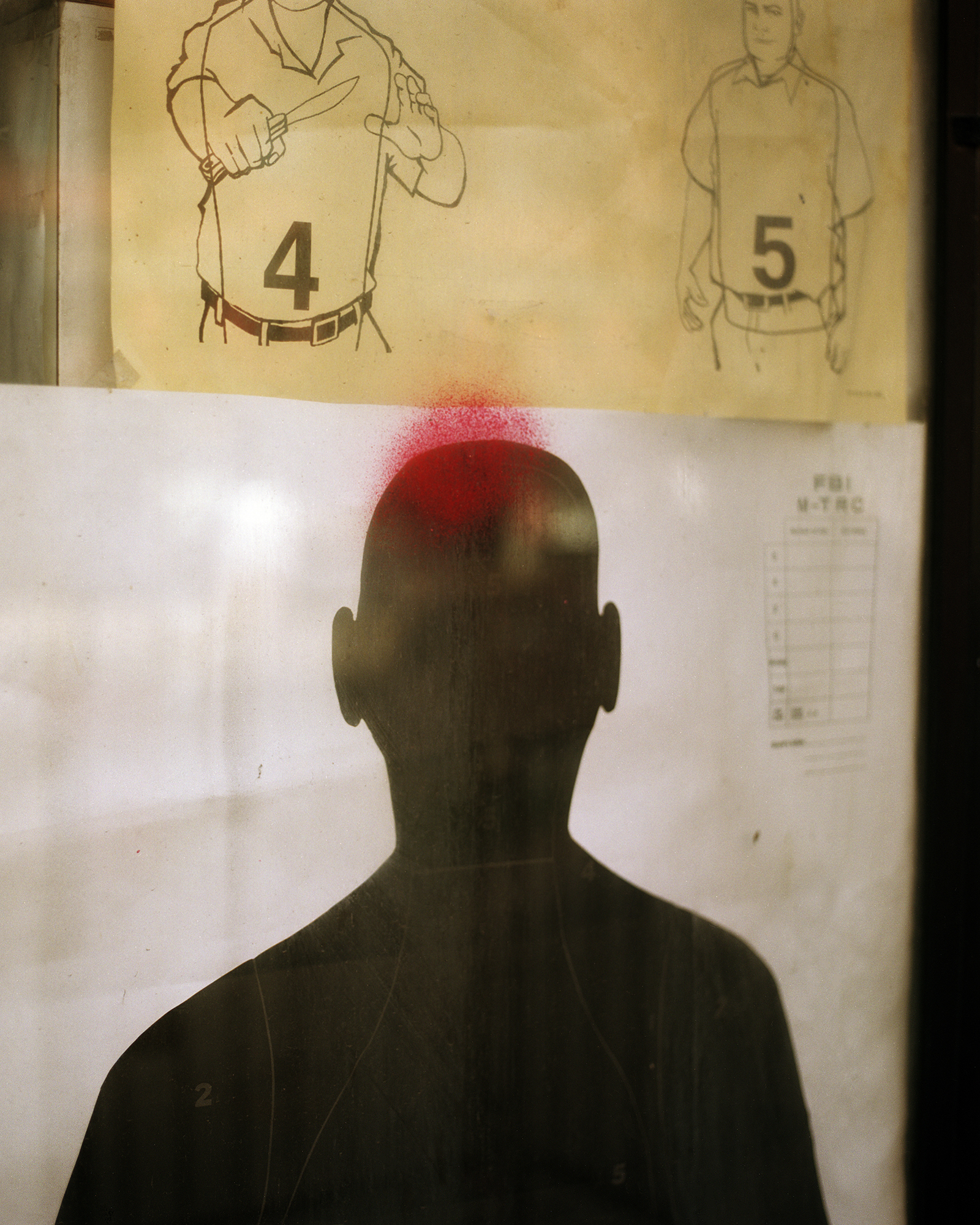

Delaney: In some of your work, anonymity weighs heavy on the image. It feels like something with volume that you could hold in your hand. Simultaneously, that anonymity draws attention to the reality of the work ultimately being a flat image – we are not granted the reveal that conventions of continuity have trained us to expect. This is just my reading. Can you speak to how you conceptualize the visual ellipses in the images you make?

Jun: Even when people know that I’m photographing them, I find myself going out of my way to inject some sense of anonymity—an obstruction, a gesture, a turn—and I feel as if it relates to the active removal of “place” that I mentioned earlier. The anonymity of the subjects help to make the composition less about the actions of a specific person or group, but more about how the subject is occupying the space around them, as well as the visual form which manifests from that almost-floating presence. When I’m walking around, I’m drawn to that same sense of form and visual question mark—a vague sense of tension or unease—but again, I never think about it explicitly while taking the picture. Rather, being able to rediscover that mystery through editing is where the photograph really comes into its own, and part of that occurs by looking at the picture months or years after the fact, when the sensation and feeling of the photograph has subsided and I can evaluate it more objectively. It also helps that I’m naturally shy and self-conscious when I’m out photographing; I’m much more of a passive observer, and I try to avoid provocation and disturbance of the scene whenever I can.

Jun Tan

Delaney: I find this idea of temporal distance between the initial production and later evaluation of images incredibly compelling. With this aspect of your process in mind, does the image become a purely visual object at some point? Does the optical quality come to replace the subjective experience you had at the moment of capture?

Jun: By putting that distance between the sensation of making the image and the image itself, I’m trying to mimic the feeling that I have when I look at other people’s pictures—to be able to start interpreting by reading just the image and what it depicts, without the influence of emotional attachment or the excess information that comes with looking at my own work. This is not to say that I want my work to be purely visual; I’m not quite sure that a photograph ever really loses its ability to elicit memory and sensation, and it would certainly be less interesting if that was the case. Rather, it’s about being able to interpret the work unencumbered by the subjective parts of image-making that don’t necessarily appear or matter to the viewer. Looking at my own work in this way is refreshing; not only finding images previously discarded that now have a sense of longevity, but also realizing that photographs that I once liked (or felt great about while making) have become less interesting—both outcomes are reminders that my process and my way of looking are evolving, but perhaps what drew my eye years ago shares some common thread with what I see today, and what I will see tomorrow.

Delaney: Who or what are your biggest influences, creatively and personally?

Jun: I am not necessarily sure if I see a difference between the two types of inspiration; looking at and perceiving the world is a simultaneously creative, personal, and intrinsic act. In that sense, I am constantly enriched by and in awe of Teju Cole’s work in photography and writing, and the uncanny way he explores the human condition, weaving deep, dense connective tissue with dancer-like delicacy and grace. Similarly by photographers of the vernacular, making images of the world’s that are askew and tenuous: Luigi Ghirri, Rinko Kawauchi, and Robert Adams come to mind. And those who make deep, delicate, intimate work bringing you close to the subject who, despite your proximity as a viewer of these tender images, remain shrouded in a mystery that can never be penetrated; Sam Contis, Deana Lawson, John Edmonds, Aubrey Trinnaman, Mark Steinmetz, and so many others. But most of all, the person who had a sense of looking closest to my heart was Jason Polan, whose sense of curiosity and openness to the world—and to New York in particular—strengthens my vision every single day, and reminds me to try and notice all the things that pass by.

Jun Tan

Delaney: I know you also draw as part of your broader creative practice. How do your multiple modes of creating images interact and how does that affect your work?

Jun: Drawing feels like an inversion of photography in my broader practice of looking at the world—I’ve read interviews with other photographers where they say the camera is a license to scrutinize things, but for me, I feel far more free sitting down somewhere for an hour and just sketching without the self-consciousness I have when it comes to walking around photographing. I say shadow, as well, because while I’m able to make pictures of those close to me, I find it impossible to draw a picture of someone I am familiar with, because I’m no longer depicting just what I see; there’s a subconscious desire to draw someone you know in a way that they will recognize and see as themselves on a piece of paper as a specific entity. Making drawings of strangers, meanwhile, feels like a more pure form of looking and taking in the world as it is. The visual associations created feel more intimate and are mostly known only to the self; the photographs might be able to elicit a memory or a reaction from the viewer, but the drawings are for myself, the things I saw, and the way I saw them.

Delaney: In making selects for sharing your work, what do you look for? Does the platform of publication affect your decisions?

Jun: The feeling of a door left slightly ajar, a sliver of light peeking through and expanding outwards. In all seriousness; I feel as if I’m in a transitional phase between a compulsion to share new work all of the time, where sharing and having people see the work become a motivation to making the work itself, and where I’m at currently—taking my time with the things that I share, taking away the implicit expectation that something being posted is new or recently made, and trying to make work and have a creative process that exists independently from a desire to be seen and recognized. So whereas before, finding work to share felt like “here’s a cool thing that I want you, the audience, to enjoy,” now the process is a little more authentic, and maybe I’m able to hone in on something more specific with what I put out into the world. Part of that has to do with taking a deeper look at my archive during this year, where the sudden combustion of nostalgia and uncertainty has created interesting threads between old work and new. The other side of that change is my relationship with Instagram—which really drove my evolution from purely wanting to be seen, into someone that maybe takes a little more security in the value of the work, my own feelings about the photographs, and prioritizing the process itself over the endgame of putting it out into the world.

Jun Tan

Delaney: Finally, any visions for the future? What do you see next for yourself and for the people closest to you?

Jun: There’s a lot of uncertainty and dread. Even so, I feel as if the world hasn’t lost that sense of base visual interest that keeps going—a privileged concern in and of itself. Yet there is some reassurance in being able to walk the same routes and see different things every time, in cherishing and uplifting the time I have with the people closest to my heart, in trying to be kind and doing the best for others, and in being here, taking it all in and looking, day after day after day.

____

Jun Tan is a photographer who lives and works in New York City.

Delaney Holton is a PhD student in the Department of Art & Art History at Stanford University. She works on modern and contemporary art with a focus on transnational Asian/American artists and filmmakers. Interests include the relationship between landscape, placemaking, and identity formation; the socio-political functions of extra-institutional artist networks and art spaces; and playfulness in art writing.