-

Kevin Williamson & Lauren Comerato

In conversation-

⍱ ⍱ ⍱ ⍱

⍱ ⍱ ⍱ ⍱

Lauren Comerato: How did you first get into photography? What was the catalyst for your practice?

Kevin Williamson: I first started photography in high school, and I was strictly interested in making landscape photographs. My family has always spent a lot of time outdoors, so making photographs of nature was a really easy way for me to start. It wasn't until I got to college that I truly started to think about photography as art. I began to develop a more critical eye, and my professors and peers pushed me to think deeply about the landscapes that I was photographing. I was starting to think about peoples' relationship to the land, and I started making photographs of my family in the landscapes. At first, making pictures of my family felt like a revolutionary idea. I had never really made portraits before, and I absolutely loved how I could begin to tell stories by pairing the portraits and the landscapes. Ever since then, family has been a huge part of my work.

LC: How did the body of work New Life come to be?

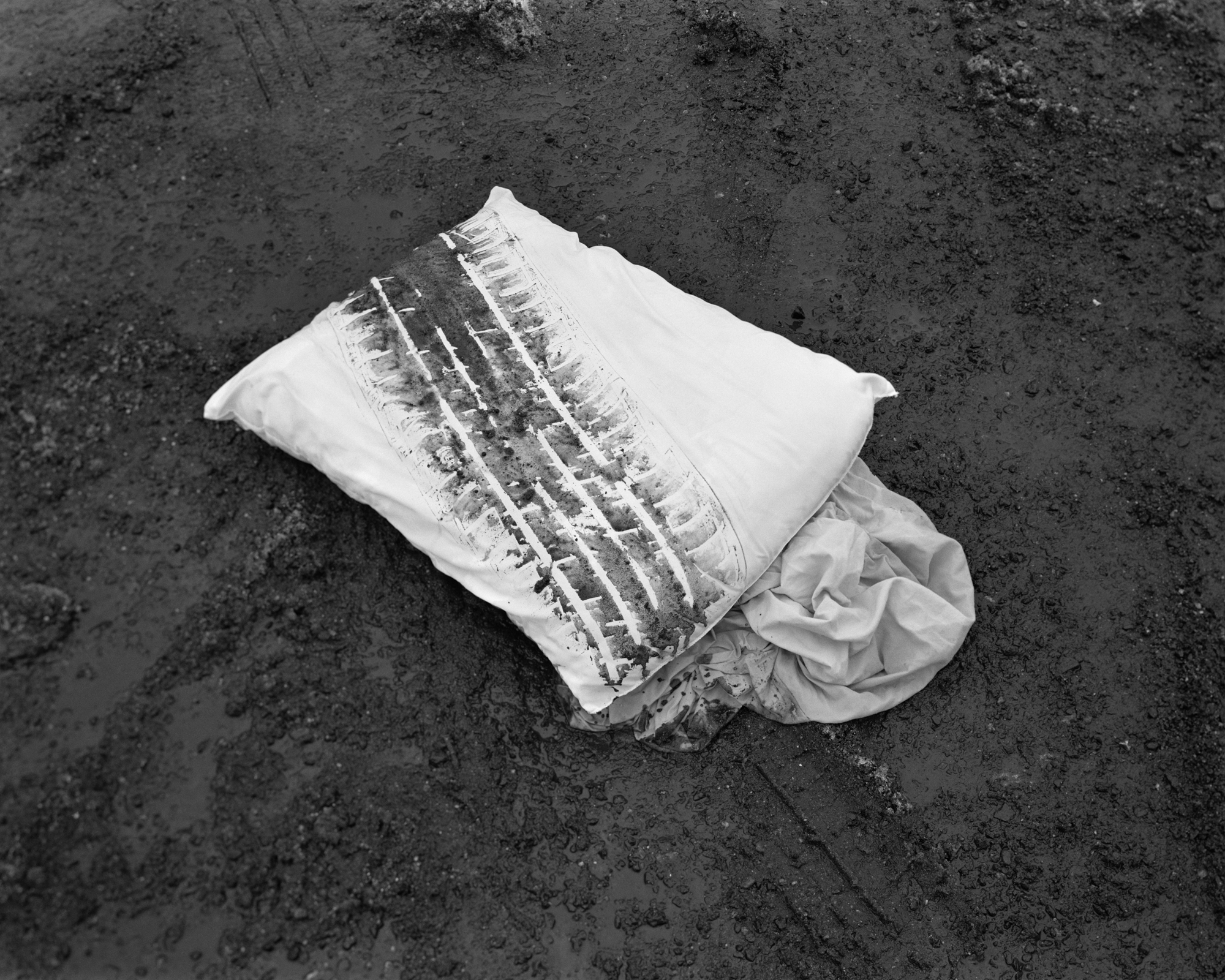

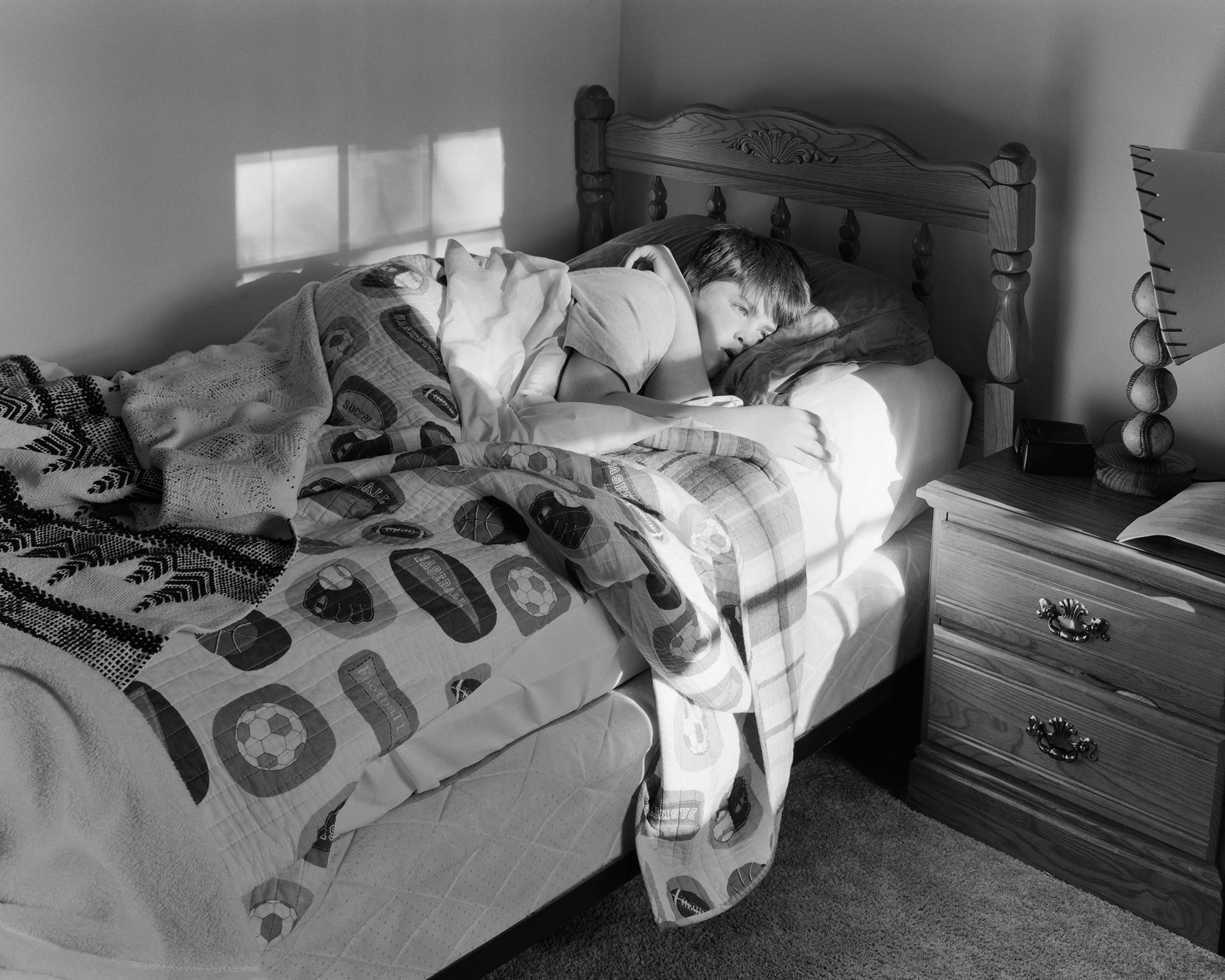

KW: This project was the result of my frustrations with the expectation that photography should always represent the truth. Ultimately I was tired of looking for stories to tell, and I wanted to create some stories of my own. When I first came up with the idea for New Life, I was reading a lot of short stories by Raymond Carver. His depictions of small towns in the Northwest and the people who live in them really resonated with me, and I began to think about what it might be like if I had grown up in one of those towns. In some ways I began to think of photography as if I were a writer. I gave myself the freedom to build the town of Fallton from the ground up. I would come up with names for the places and people that I photographed, and it was a process that really stimulated me creatively. It was a lot of fun to make pictures all over the place and then figure out how to put them together so that they felt like they were all made in one town. I then came up with the idea to tell the story of Fallton through the eyes of a teenage boy who had lived there his whole life.

LC: I notice in New Life there are some old photographs, and I am aware that these are glass negatives. Can you talk about how you stumbled upon these images and why you integrated them into your work?

KW: Before they became a part of this project, the glass negatives were something that I was collecting simply as historical objects. The first negatives that I came across were at an antique shop, and there was something magical about holding a picture that was probably 100 years old. It's a special experience holding an antique glass negative up to the light. As I was making this work, I realized that the negatives I was collecting could serve as a false history of the town. I can't say for sure, but I believe that most of the negatives I have are from the late 1800s to the early 1900s. This was a time when the logging industry was beginning to decline in the Northeast, so these pictures could serve as timely historic documents in the history of Fallton as a declining logging town. After I used the negatives that I already had, I started to search ebay for specific negatives that I thought could add to my story. I really wanted to use the negatives as a way to fill in some parts of the narrative that I couldn't with modern day pictures, so I began to be a little more specific about what I was looking for once I knew that I wanted to use them.

LC: I have been able to watch your practice grow for four years now and I love getting to see how your practice has evolved to include these fictional elements. I believe writing has always been a strong point for you, so seeing you integrate these two interests together has strengthened this body of work for me. I really don't see them as separate; they are that well integrated. What were some obstacles you faced when creating this body of work? Did you anticipate any of the challenges?

KW: The biggest obstacle was probably the fact that I was an outsider to the places that I was photographing. Being someplace completely new was exciting, but it also made it really easy to take pictures that look like they were made by an outsider. I had to imagine myself as a resident of the place, and then I would start to make the kinds of pictures I was looking for. I really tried to stray away from the kinds of pictures that someone would make if they were just passing through. A lot of my successes came from chance meetings with people. We would talk and I would try to learn a little about their experiences, and sometimes a picture would come out of it.

LC: These photographs are all in black and white, what's the reasoning behind that? Do you also take color photographs?

KW: I chose to work in black and white for this project because of black and white's relationship with the past. I was thinking of Fallton as a historic logging town, and I wanted to make pictures that reflected that history. Black and white pictures make people think about times when pictures were only made in black and white. I wanted that historic background in every picture I made, even though it's clear that I'm showing the present. I've worked in color for other projects and I'm definitely not opposed to working in it again, but black and white felt like the right choice for this work.

LC: When you are stumped or hit a creative block, where do you look for inspiration?

KW: I most often look to writers when I hit creative blocks. I've been reading through some of Cormac McCarthy's books lately, and it has been really great to study how people outside of the visual arts tell stories. When you get inspired by the work of other photographers, you can sometimes run the risk of copying their pictures. When I get inspiration from writers, there's a transformation that happens in the translation of the written word into visual art. Right now I'm reading through Jack Kerouac's On the Road, and I came across this line. He writes, "The bus roared on. I was going home in October. Everybody goes home in October." I can't even really put my finger on why that line is so profound to me, but I think it has something to do with longing. Hopefully I can make a picture or two out of it.

LC: What is one way your artistic practice has changed by making this body of work?

KW: I am now way more open to incorporating different things into my artwork. Previously, I had thought of my practice as strictly photography, but in New Life, I began to think about the written word as well as incorporating some found imagery. This idea is only in the beginning stages, but I am starting to think about treating this body of work as a journal. I think that it would have to be a loose, rough book form, which is also something new for me. I am really passionate about photo books, and I think that there might be something worth exploring in terms of how I can get my short stories and pictures to live in the same space.

LC: What contemporary artists do you consider your kin?

KW: I really fell in love with the work of Justine Kurland when I first started school at MassArt. Her book Highway Kind completely changed the way that I thought about photographic projects. The way that she pairs pictures of her son with photographs of their travels around the United States is so beautiful; it's a perfect combination of relationship and land. Her newly released Girl Pictures is also pretty great too. Larry Sultan was another one of my earliest influences. I am blown away by the way that he writes about the experience of being a photographer of family in his book Pictures From Home. It's so personal, and he doesn't hold back when it comes expressing doubts about his pictures - something I'm sure all photographers can relate to. More recently, I've been getting into the work of Raymond Meeks, Matthew Genitempo, and Andrea Modica. Raymond Meeks has a dreamy, poetic style that I really admire. Matthew Genitempo's book Jasper feels like it's made in the same vein as my work, his photographs of hermits in the Ozarks are something special. I just got introduced to Andrea Modica's book Treadwell, and its portraits have really inspired me. There's a great story of family and love that comes out in those pictures. Lastly, I feel like I will always be inspired by Robert Adams. His photographs ground me and make realize why I got into photography in the first place - beauty of light, and additionally, love.

LC: What is one word you would use to describe your artistic practice and why?

KW: Contradictions. Specifically, I thought a lot about contradictions while making New Life. People are full of contradictory thinking. It's what makes them real, complex people. Some of my own contradictory thinking is what inspired this work. When it comes to conservation, I think it's really easy to say that we should stop cutting down trees and taking things from the environment, but I also have to recognize that everything I have comes from the environment. It's a moral struggle to figure out if it's even possible to find a solution. This struggle is where most of my ideas for pictures come from.

Additionally, I have been thinking a lot about contradictory double meanings in my photographs. Water begins to represent death rather than life in some of the pictures, especially after reading the story I wrote where the boy's brother almost drowns. Another contradiction that is at the core of the work is the subjects' simultaneous hope for the future while still holding onto the past.

LC: It's been great talking to you about your work, Kevin. What's next for you?

KW: Thanks for the insightful questions Lauren! I don't think that I am finished with this project yet, so for the time being I'll be making more pictures to go along with these. With the help of my Dad, I just finished building a darkroom in my basement. I am planning on making an edition of gelatin silver prints of this work, and hopefully I can find a place to show them!

____

Kevin Williamson (b. 1998) is an artist and educator from Ossining, New York. In May 2020 he completed his BFA in Photography and Art Education from Massachusetts College of Art and Design and graduated with Departmental Honors in photography. In 2018, he was a recipient of the “Connors Prize” within the Gertrude Kasebier awards at Massachusetts College of Art and Design. In 2020, Kevin was a selected recipient of Fujifilm's "Students of Storytelling" prize. Mainly using a large format view camera, Kevin makes intimate photographs of his family, friends, and stranger’s interactions with the landscape. Growing up in the Hudson Valley, Kevin has spent much time exploring the rolling hills and bodies of water that surround his home. Living there has had a profound impact on his work, and he uses photography and writing to portray his continued love for the natural world. This place, situated between the urban and the rural, has allowed Kevin to think about the complications that come with human usage of the land. Relationship to person and place are very important in his work, and throughout his projects he has explored how both personal and collective identity are informed by place. More recently, Kevin has been incorporating fiction into his photographic work, as he explores the life of a boy growing up in a historic logging town.

Lauren Comerato (b.1997) is an artist and educator living and working in Framingham, MA. She recently graduated with the class of 2020 from Massachusetts College of Art and Design with a BFA in Art Education and Fibers. She graduated with Departmental Honors in Art Education, as well as Academic Honors. She is the recipient of the 2020 John Crowe Award from the Art Education department and the Barbara L. Kuhlman Scholarship for Fiber Artists. Lauren’s body of work explores her love for materials and their relationships with her family. Growing up around a father and brother who are both electrical contractors, she developed a deep appreciation for materials that are industrial and often seen as mundane. Contrast to that, her latest body of work explores the fiber crochet traditions that have been passed down through the women in her family. Everyday objects such as blankets and doilies are seen in a new context and merged with blue collared materials used in construction. Her love for laborious materials is becoming more evident as she is currently exploring her relationship with weaving and the ways in which she can push the material to its full potential.