-

Marissa Iamartino & Kelsey Sucena

In conversation-

⏧ ⏧

⏧

I use my left hand to pull a wooden crate from the corner of my room. Hadn’t even taken off my jacket yet, but that’s the nature of most returns home: scurrying through the loud storm door after driving back from wherever, bouncing between walls for some silly immediate action. Winter shifts everything into a constant darkness and there’s not many street lights Here. My drives Here often parallel the river - The Water - the reason, likely, why I ended up Here. The gravitational pull of The Water downwards. The gravitational pull of My Own Water.

The crate was to hold the chicken tajine and pita that’d been quickly heating in the oven. No furniture yet, and so I eat my meals on the floor atop a pile of tattered rugs I’ve grown attached to over the years. The jacket, my favorite: fuzzy / navy / black with two white blobs on the back. A big owl next to a full moon. It encapsulates my frame into a shapeless shield of uncertainty, the unspoken requirement in my wardrobe, and the sleeve singes in the oven as I pull pita off the rack.

I set the frame of Kelsey next to my hot pan of tajine, both balanced atop the crate, and we struggle with the internet, the sound, the disconnection for a minute until both of our grins are synchronous and in-real-time. Their eyes are sparkling as always, framed in upturned red glasses, and even locked in a screen, their soothing nature reverberates through molecules, exploding the blue light into yellow. The harmony of a long winded “Hiiiiiiiiiiiiiiii!!” commences, and we chat as I shovel broth-soaked pita down my throat.

During that evening, we set our parameters for this conversation, which are as follows: All conversation is to be held through a text message thread. 2. All conversation will be conducted call-and-response style. 3. Direct conversation, sources, images, new writing, questions, etc are all fair game. 4. Maximum 3 texts per day to be sent by each person. 5. The conversation will begin on Sunday December 13, 2020 and will last for one week.

The crate was to hold the chicken tajine and pita that’d been quickly heating in the oven. No furniture yet, and so I eat my meals on the floor atop a pile of tattered rugs I’ve grown attached to over the years. The jacket, my favorite: fuzzy / navy / black with two white blobs on the back. A big owl next to a full moon. It encapsulates my frame into a shapeless shield of uncertainty, the unspoken requirement in my wardrobe, and the sleeve singes in the oven as I pull pita off the rack.

I set the frame of Kelsey next to my hot pan of tajine, both balanced atop the crate, and we struggle with the internet, the sound, the disconnection for a minute until both of our grins are synchronous and in-real-time. Their eyes are sparkling as always, framed in upturned red glasses, and even locked in a screen, their soothing nature reverberates through molecules, exploding the blue light into yellow. The harmony of a long winded “Hiiiiiiiiiiiiiiii!!” commences, and we chat as I shovel broth-soaked pita down my throat.

During that evening, we set our parameters for this conversation, which are as follows: All conversation is to be held through a text message thread. 2. All conversation will be conducted call-and-response style. 3. Direct conversation, sources, images, new writing, questions, etc are all fair game. 4. Maximum 3 texts per day to be sent by each person. 5. The conversation will begin on Sunday December 13, 2020 and will last for one week.

⏧ ⏧

⏧

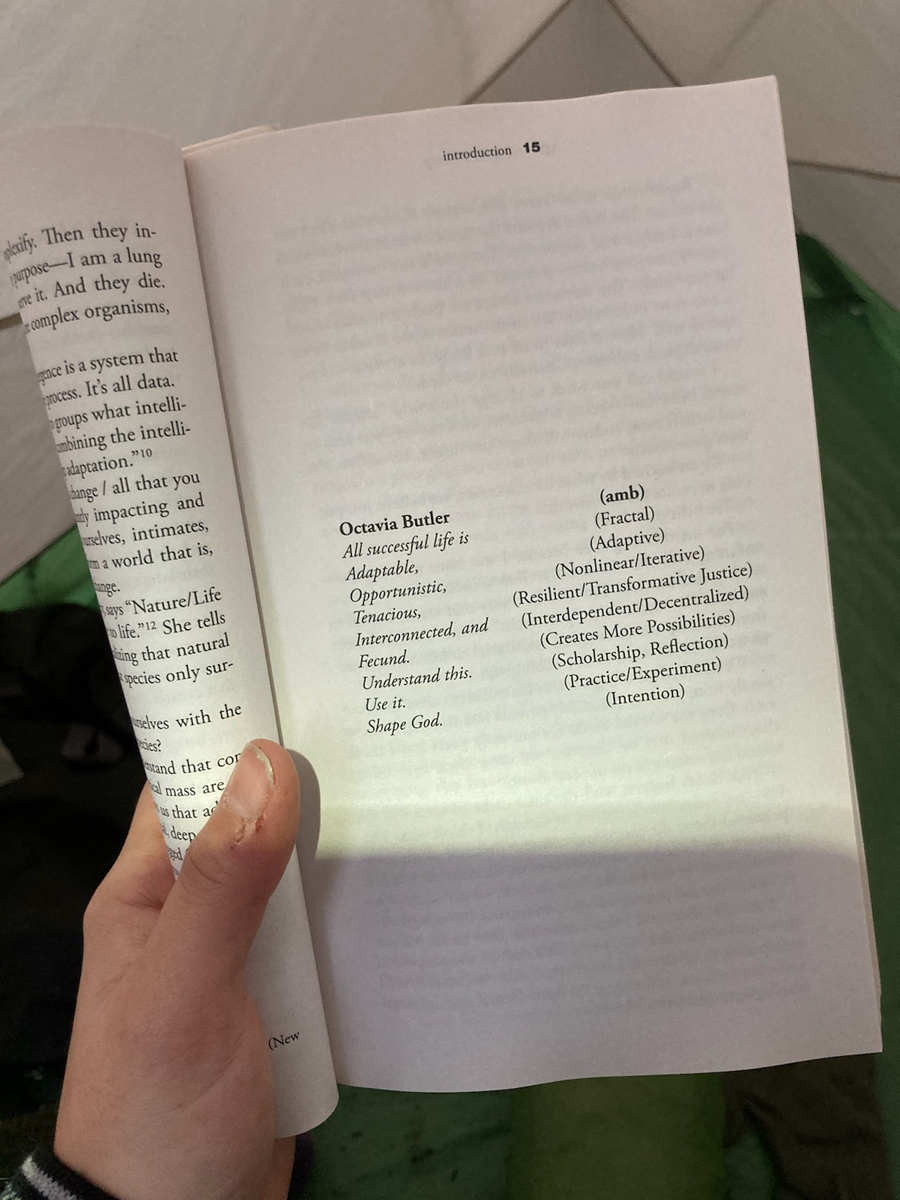

MI: hi Kelsey. i hiked the Appalachian Trail yesterday to camp in a spot called Sages Ravine. haven't camped alone in a long while -- it felt very alone but very good -- read some of adrienne maree brown's Emergent Strategy while trying to calm my nerves amongst coyote howls.

Marissa Iamartino

KS: Marissa! It's so good to hear from you. I've been looking forward to this conversation.

Your message has me waxing nostalgic about my own experiences with both Coyotes and adrienne maree brown's work. Thinking back to some time on the road in Badlands, or Big Bend, or Joshua Tree. Coyotes are fascinating to me. In the last few years they've been slowly migrating out to where I am on Long Island, and this has had folks in a state of panic. Long Islanders see it as the unbelievable intrusion of an apparently uncontrollable force.

But Coyotes are also cooperative creatures, and I think in terms laid out by Brown in "Emergent Strategy, that their appearance within my anxious little suburb can help to model new ways of living, especially for those who feel alienated by suburbia.

That's such a lovely book though. I think it continues to buttress me against the political dread I've been feeling. I'm curious to know what your experience has been reading it? And especially what it must be like to read it on the AT.

![]()

MI: my experience with the book, like my experience with most things, has been thoughtfully sporadic. in the introduction, brown writes something like, "this can be read non-linearly!" (exclamation point included ) and i took it upon myself in that moment to begin thumbing to passages at random. it felt relieving to have her permission.

i love the idea that my engagement with text arbitrarily relates to outer forces and happenings, how coyotes and apricots and Octavia Butler and texting you this at the laundromat will forever be tied in my brain. i just watched my clothing spin its last spin through the circular washer window, which is the first time that’s ever happened.

a few moments i’ve underlined:

"adaptation reduces exhaustion." 71

"___ as weeds and fungi, the incomprehensible scale, the clarity of identity, excites me." 9

"a visionary fiction is the way to practice the future in our minds, alone and together." 197

"some people are comfortable believing -- in heaven, in socialism, in someone else's thinking. that's never quite worked for me. i learn experientially. i am so far only convinced that change is divine and constant." 56

i took a bit of a sigh at the last line there. i'm often strongest in my moments of curiosity. whether making images or deciding to head out in the woods for a few days, there's something about unknowing - about luck or chance - that endlessly excites me. slowly, i'm learning how to set up my experience of the world so i get to have more of that... it feels greedy, in a way. like purposefully falling into a well just to see if you can get out. or to collect someone else’s pennies at the bottom.

KS: I'd like to hold onto this for a moment, but pivot just a bit. Because I deeply resonate with everything you're expressing about your relationship to the world. To that which is unpredictable. To ritual and to pattern recognition. At the same time I think it's important to dig a bit deeper and to anchor our conversation within the photographic.

All of that is to say that I'm interested in making connections between what you've said here, and what you express through your work and practice. And to be clear I find myself thinking that the connection between your projects and these observations are obvious to me. But let's take a moment to situate these thoughts within practice.

Can you describe where you are now within your practice, especially as you enter the final production phases of your thesis project?

MI: my practice is about sustaining behaviors through time -- and despite life's undulations and my own impulsiveness, making / writing / processing / exchanging ideas communally are some of my consistencies. making fills me up and moves my mind in pleasure-seeking ways. a serotonin high. i think tumbling into knowledge, including self-knowledge, is really its own form of pleasure.

i'm centered as a lens-based artist and have expanded outward from there. from my first interactions in a darkroom, i was completely captivated by photography... it was the first science that had an understandable logic, the first type of history i felt connected to. with photography, the idea of work or ‘perfecting the craft’ isn’t actually about perfection, it’s more about learning how to move your hands in the dark.

i'm currently doing a lot of learning and unlearning in my practice. existing within institutions has led me to understand a very specific language of art and photography -- and as i continue to grow as a maker, i’m tearing good images apart while also trying to stay true to my sensibilities. i've always felt strongly about color, about working intuitively with inconsistent methods/tools, and about relinquishing ownership. even in their ubiquity, images are sacred. i mean, they’ve only existed in the forms we know for less than two hundred years, and digitally - much less. no matter how much time i spend working with or writing about pictures, the pictures are never really mine.

my thesis work is shifting rapidly at the moment, i wouldn't even use the phrase final stages (nowhere near, truly) but i am taking a deeper look into my family's history. i’m third generation Italian-American and have had a beautifully strange back-and-forth relationship with Mezzogiorno over the years. i’m interested in that identity space, what it means socially and politically in the United States right now, and overall, am unraveling some complicated experiences with tradition, gender and sexuality, lore, and generational disconnect.

![]()

Your message has me waxing nostalgic about my own experiences with both Coyotes and adrienne maree brown's work. Thinking back to some time on the road in Badlands, or Big Bend, or Joshua Tree. Coyotes are fascinating to me. In the last few years they've been slowly migrating out to where I am on Long Island, and this has had folks in a state of panic. Long Islanders see it as the unbelievable intrusion of an apparently uncontrollable force.

But Coyotes are also cooperative creatures, and I think in terms laid out by Brown in "Emergent Strategy, that their appearance within my anxious little suburb can help to model new ways of living, especially for those who feel alienated by suburbia.

That's such a lovely book though. I think it continues to buttress me against the political dread I've been feeling. I'm curious to know what your experience has been reading it? And especially what it must be like to read it on the AT.

Kelsey Sucena

MI: my experience with the book, like my experience with most things, has been thoughtfully sporadic. in the introduction, brown writes something like, "this can be read non-linearly!" (exclamation point included ) and i took it upon myself in that moment to begin thumbing to passages at random. it felt relieving to have her permission.

i love the idea that my engagement with text arbitrarily relates to outer forces and happenings, how coyotes and apricots and Octavia Butler and texting you this at the laundromat will forever be tied in my brain. i just watched my clothing spin its last spin through the circular washer window, which is the first time that’s ever happened.

a few moments i’ve underlined:

"adaptation reduces exhaustion." 71

"___ as weeds and fungi, the incomprehensible scale, the clarity of identity, excites me." 9

"a visionary fiction is the way to practice the future in our minds, alone and together." 197

"some people are comfortable believing -- in heaven, in socialism, in someone else's thinking. that's never quite worked for me. i learn experientially. i am so far only convinced that change is divine and constant." 56

i took a bit of a sigh at the last line there. i'm often strongest in my moments of curiosity. whether making images or deciding to head out in the woods for a few days, there's something about unknowing - about luck or chance - that endlessly excites me. slowly, i'm learning how to set up my experience of the world so i get to have more of that... it feels greedy, in a way. like purposefully falling into a well just to see if you can get out. or to collect someone else’s pennies at the bottom.

KS: I'd like to hold onto this for a moment, but pivot just a bit. Because I deeply resonate with everything you're expressing about your relationship to the world. To that which is unpredictable. To ritual and to pattern recognition. At the same time I think it's important to dig a bit deeper and to anchor our conversation within the photographic.

All of that is to say that I'm interested in making connections between what you've said here, and what you express through your work and practice. And to be clear I find myself thinking that the connection between your projects and these observations are obvious to me. But let's take a moment to situate these thoughts within practice.

Can you describe where you are now within your practice, especially as you enter the final production phases of your thesis project?

MI: my practice is about sustaining behaviors through time -- and despite life's undulations and my own impulsiveness, making / writing / processing / exchanging ideas communally are some of my consistencies. making fills me up and moves my mind in pleasure-seeking ways. a serotonin high. i think tumbling into knowledge, including self-knowledge, is really its own form of pleasure.

i'm centered as a lens-based artist and have expanded outward from there. from my first interactions in a darkroom, i was completely captivated by photography... it was the first science that had an understandable logic, the first type of history i felt connected to. with photography, the idea of work or ‘perfecting the craft’ isn’t actually about perfection, it’s more about learning how to move your hands in the dark.

i'm currently doing a lot of learning and unlearning in my practice. existing within institutions has led me to understand a very specific language of art and photography -- and as i continue to grow as a maker, i’m tearing good images apart while also trying to stay true to my sensibilities. i've always felt strongly about color, about working intuitively with inconsistent methods/tools, and about relinquishing ownership. even in their ubiquity, images are sacred. i mean, they’ve only existed in the forms we know for less than two hundred years, and digitally - much less. no matter how much time i spend working with or writing about pictures, the pictures are never really mine.

my thesis work is shifting rapidly at the moment, i wouldn't even use the phrase final stages (nowhere near, truly) but i am taking a deeper look into my family's history. i’m third generation Italian-American and have had a beautifully strange back-and-forth relationship with Mezzogiorno over the years. i’m interested in that identity space, what it means socially and politically in the United States right now, and overall, am unraveling some complicated experiences with tradition, gender and sexuality, lore, and generational disconnect.

Marissa Iamartino

KS: I know the feeling. Despite my constant suspicion of photography as this atomizing force, and the tension I experience from life in my past within Northeastern academia, photography still feels like this important thing. It's so easy to fetishize, to romanticize, and those formative moments in the darkroom make that hard to avoid, but despite my suspicions I often think about how photography has shaped my relationship to the world in profound ways. How it has enabled me to exist improvisationally, and to construct personal histories.

Lately I've been thinking about photography and depression. In particular I imagine my relationship to the medium being in some way related to symptomatic memory loss associated with depression. This is all to say that the experience of loss, of memory loss in particular, has always driven me to make photographs.

Do you ever feel that way? In particular I'm thinking about what I know of you and of your work. As you've mentioned, some of your process feels driven by a desire to understand generational disconnect, and I know that you're undergoing a myriad of changes right now. Where does that leave you and your camera?

Kelsey Sucena

Marissa Iamartino

MI: i'm moved by that connection of memory loss and depression. i've actually experienced memory loss for years and i've always quietly attributed it to how my brain handles trauma. loss can be both scary and freeing, but there's something fascinating about the idea of photography as an indirect translation of life. just as objects hold energy, images do too: they shape our understanding of histories, futures, and ourselves.

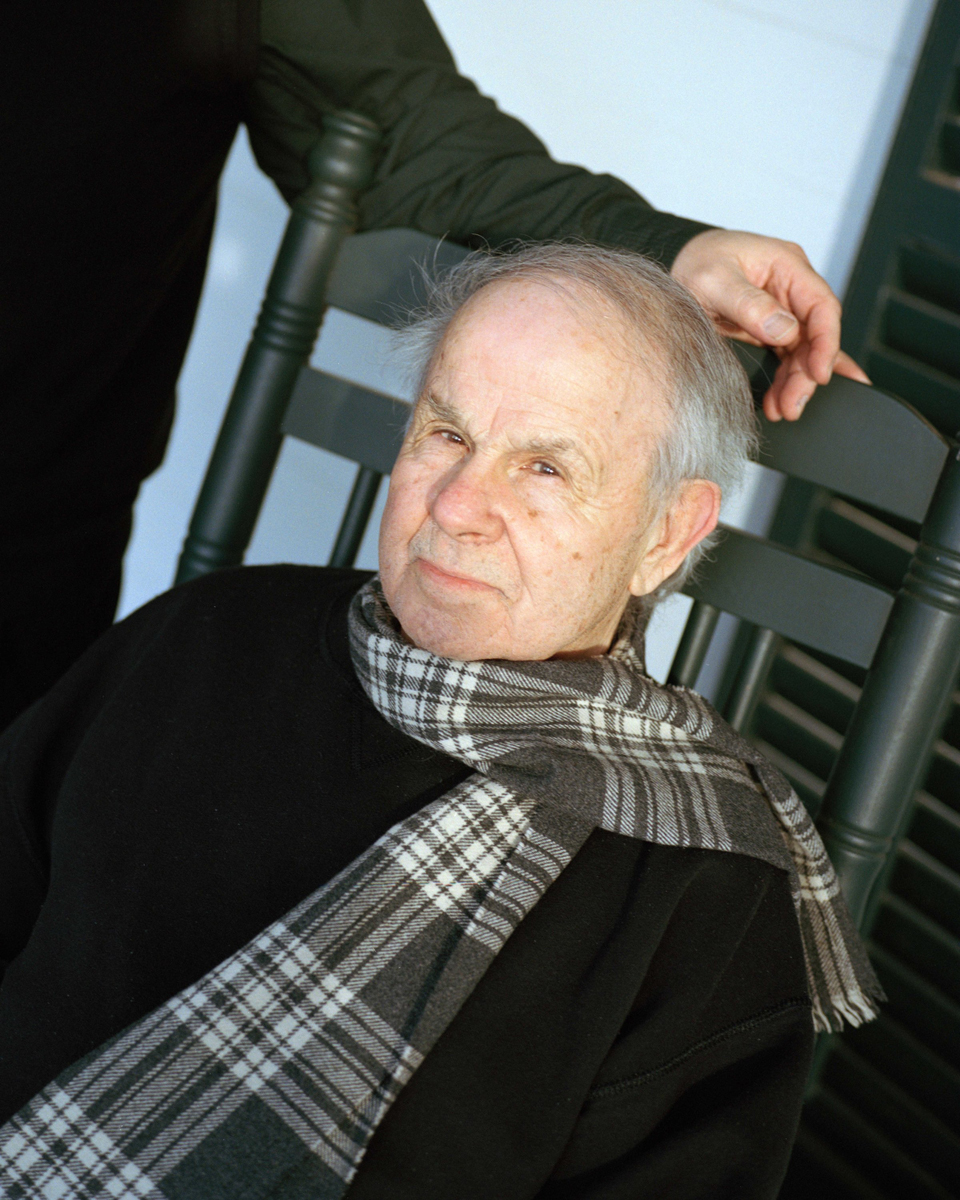

i AM going through a number of compounding shifts right now, in a way that feels familiar and breathtakingly new. my grandfather, the patriarch of my family, sadly left earth a few weeks ago and with him goes so much knowledge. he survived Polio as a child and grew up between here and Italy. there was always something hiding or unresolved in his watery eyes.

i’m thinking a lot about connectivity - the unexplained, spiritual, and painful - that transcends time and space and bodies and reason. i've been traveling back and forth to Italy since i was a kid and about five years ago, i was given my great-grandfather’s 1954 Leica M3. he also loved photography and flora and lemons, and in my frequent travels to and from Italy, in his space, i was making images with his camera and collecting a stash of film that sat latent for years. the film is no longer latent, and i’m puzzling together my images alongside his.

Kelsey Sucena

KS: I don’t talk much about this anymore, but I used to study Buddhism. I bring this up because it feels relevant here, as it always has, to photography, death, and interconnectivity. I once read Chogyam Trungpa Rinpoches “The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying”, and found myself spiraling as I struggled to dislodge my photographic practice from what I saw as desire, attachment, grasping, and a fear of death. I thought that photography could act as a form of meditation, or that it could otherwise emulate an interconnected world, but I found that on its own it usually fell short. Even more so I found this goal to be a bit counterproductive, fueling new desires and frankly creating fiction between my practices (artistic and spiritual).

What I thought back then, as a fearful undergrad, was that photography could only serve to outline death. I realize now that it’s so much more than that. Photographs have this capacity to hold a kind of talismanic energy. They are objects, impermanent themselves, which speak to more than just our fears.

I’ve got this one picture of my father, covered in sheetrock dust. I took it just a month after finally coming out to a friend for the first time, and just a month after graduating from college and moving back home. My father had decided that this was the best time to tear up my childhood room, replacing their baby blue surfaces with plain white walls. I used to be bitter about that transition, but my father’s gone now and it’s hard to be bitter about something so trivial. Looking back on this photograph I can recognize the way in which it has become its own kind of organism, evolving and growing and turning into dust. I appreciate it for this. It reminds me that even in death our relationships can still evolve.

Kelsey Sucena

Marissa Iamartino

MI: i love your framing of 'the photograph as talisman'. i feel we both seem to be speaking of images in a physical sense - tangible, tactile, or maybe just palpable in the mind. do you have any specific images that you've been able to sustain a relationship with over the years? i use this one Wolfgang Tillmans image of peeled citrus as a constant palette cleanser.

i also believe relationships can evolve in death, and even in absence. for me, absence is really just a quieter form of death. the beginnings of photography defined images as a stand-in for connection, though the inevitability of the object’s failure is what has allowed it to move past its original intentions. i think about the tiny Daguerreotypes tipped into velvet lockets or booklets that people first used to hold onto pictures of soldiers. we still do this with our loved ones - honor them in image - but what does it mean for photographs to transcend?

i guess i think of religion in a similar way to food or language or music, through a quasi-anthropological lens. i like to know about the movement of people and ideas and resources. maybe it’s because i grew up listening to my dad and brother argue about word etymology, Star Trek, and Byzantine history -- but your dipping into Buddhism makes me think about my own spiritual practice and how it mirrors my artistic one in a breezy kind of way. i really connect with Lao Tzu and Taoism's concept of 'The River': control and lack thereof, and the paradoxical action of non-action.

KS: There are quite a few photographs which I seem to have developed relationships to over the years. Outside of my own photographs, which of course represent the most intimate photo relationships I have, there are so many photographers who I return to often. Recently I was thinking about Mike Brodie's "A Period of Juvenile Prosperity".

There's one photograph in there of a young person looking out across a sunbathed field from a train car. Their dreadlocked hair trails behind them, glowing golden in the light. Looking at it now I'm recognizing that their gender is indeterminate, but that I've always assumed they were a woman. I've looked at that photograph with a deep sense of longing and now I'm seeing that that longing is rooted in the fact that I've always wanted to be her. That imaginary “her” I had invented from this little bit of evidence. Beset against America, totally free, hopping trains.

Kelsey Sucena

Marissa Iamartino

MI: i just brought up Mike Brodie in another conversation yesterday! i love those pictures. someone told me once that he never made pictures again and now works as a mechanic. i’ve refrained from fact-checking the idea because i don’t want to crush my own fantasy of it. it’s beautiful.

America is also the backdrop for a lot of your work both in photography, as a Park Ranger, and as you navigate other personal experiences with gender and relationships. can you talk about, either presently or historically, how this backdrop has influenced your way of making work? i know Paralytic States was just released into the world a few months ago. what are you doing now?

KS: Oh, thats a good question. I think that right now I'm focused on resting, recuperating and collaborating. This pandemic has made it difficult for me to make work, and though I've made a few images (including this series of mushroom portraits), I've been more or less concerned with distributing Paralytic States and with working with other artists who may need text, reviews or whatever.

As far as "America" is concerned, there's just so much to say. When we consider America what we're considering is the diverse and complex network of communities, beliefs, values, economies and regions which emerged from the brutal history of European colonization and all of its associated institutions and structures. And the fact that this country continues to exist as a singular entity despite our monumental divides is kind of absurd, and generally indicative of the continued influence of money and power within an increasingly authoritarian state. I've always been interested in that absurdity, at times hopeful, often fearful, but generally ambivalent to it all.

I also realize that, as a photographer, I'd probably situate myself within the same "east coast" lineage as many of the photographers I admire. These are folks who, since the time of the New Deal and the rise of the United States as a global superpower, have been tethered to "America" as a complex subject, addressing it critically, reverently or a little bit of both. I'm thinking of this chain of influence from Walker Evans to Kristine Potter which I acknowledge as my own.

How about you? Where do you situate your practice historically, and what does that relationship look like?

Marissa Iamartino

MI: i feel a bit *untethered* from place in my life and in my practice -- and i think the way i make pictures can sometimes reflect that sentiment. i like the clash of divergent narratives and the tension between images that vary in tone, style, language. i've been reading a lot of books that also operate in this way, like Flights by Olga Tokarczuk, Die My Love by Ariana Harwicz, or Tristano by Nanni Balestrini.

i'm an east-coaster as well -- something i remember that was pointed out about both of us by a professor at Image Text Ithaca -- and i have a deep appreciation for understanding why things are made the way they are and in what context, although i’m definitely in a space of conscious unlearning right now. today's mood is: Fuck The Canon (except for maybe Emmet Gowin).

i enter most things through desire and for me, art-making really begins as a form of play -- that within itself being a small act of resistance. historically, i'd like to place myself alongside some photographers, sure, but also people who move, write, cook, challenge, care, make-marks, kiss, connect things, take risks. i do love Cy Twombly / have been spending lots of time with Silvia Federici's writing / revisit Audre Lorde often / am grossly obsessed with Wolfgang Tillmans / love and hate Sofia Loren in Ieri, Oggi, Domani / devour The Foxfire Books and family herbal remedies / and just finished watching Michaela Coel’s I May Destroy You. maybe it's about friction or intersectional feminism or movement through time or space or nature or connectivity or the body. regardless i’m placing those names here.

also -- currently reteaching myself to play the keyboard. has this year been a catalyst for any new skills?

KS: Well I started gardening, which was pleasant. Until restrictions were lifted and my partner and I had to return to full time work, so our garden just sort of...

And I grew my first sourdough starter, baked bread, made bagels, all until again, restrictions were lifted and I didn't have time to feed my culture so it just sort of...

Whats funny is that the quarantine seemed to give me a little glimpse into life on the other side of capitalism, and I miss that, as otherwise isolating the Spring and early summer were.

But as far as skills go, I suppose the biggest change has been my investment in fashion. I've been exercising for the first time in my life, and learning about my body. What looks good on it. What doesn't. This is the first year my wardrobe has ever been primarily feminine, which has felt incredibly validating to me.

I'm realizing that all of these skills have been both enriching, and financially/professionally/artistically unproductive, which is one thing I sort of like about them. It makes me think back to something you said in your last message.

I want to prod it a bit more, if only because I so agree and am always trying to tease out the words to explain the sentiment. I'm talking about that moment wherein you described your work as an act of resistance. Can we flesh that out some more?

Kelsey Sucena

MI: absolutely, and first i just want to say that reading about your recent endeavors brought me immense joy!

i feel deeply and gratefully connected to my communities of artists. making, whether done for the self or collectively, innately defies systems of oppression because it is so-often an act of joy. time for time's sake, effort for effort's sake, an experience of an experience, not a promise of reward -- and so in that way i see it as a possibility for shame-shattering and togethering. i especially see myself using and subverting the traditional languages of photography to redistribute energy through non-linear narratives. i often use different cameras for one body of work, incorporate writing and drawing, and create site-specific installations that are connected yet ephemeral.

i worked as a therapeutic artist in pediatric hospitals for a few years, and it was the most incredible space for learning how to collaborate, ironically, while existing within institutions that operate based upon hyper-strict rules, regulations, and practices. that time made me believe in art as connector. that process is the actual thing, that the negative space, the quiet space around the object, holds our collective understanding and that’s where meaning lies, not within the object itself.

KS: I deeply resonate with your sentiment. That art can serve as this communal, communicative space beyond the profit imperative is something which carries me through my own practice often. I too feel so grateful to have access to a community that is so driven, so concerned with image making, and also so warm and open.

At the same time I'm not at all surprised to hear about your experiences making art within the framework of institutions like hospitals. I often think that those spaces which come with the most rules, infrastructure, limitations can be spaces wherein we're forced to think most creatively. Sometimes arbitrary rules can inspire innovative rule-breaking better than the free wheeling anarcho spaces of 'art' more broadly.

That said, I'm not always convinced of the wholesomeness of art, meaning I think it's possible that we aggrandize, maybe even fetishize its potential for change. That it can serve as a space beyond capital doesn't necessarily mean that it will serve as that space. I look around at art markets, struggling as they are through this pandemic, and I'm forced to wrestle with precarity, with extortion, with extraction. Do you ever have similar reservations? And if you do, how do you navigate them in your practice?

Marissa Iamartino

MI: my own frustrations with art always seem to lead back to my frustrations with government and culture. there's such a lack of funding and support for artists in the U.S., and compounded with the 'live to work’ not ‘work to live’ mindset -- which are both shittier options than the ‘let’s just exist’ mindset, by the way -- makes it near impossible for an artist, or anyone, to survive outside of capitalist sentiments. if we have to continue to exploit ourselves to make ends meet and to cater to the rich who have historically controlled the art market AND the narrative of what is good and what deserves to be seen...well that is a bleak, bleak future for us all. and so i think half the 'job' of being an artist is navigating how to just simply make it work. finding loopholes, getting gigs, holding space for each other, managing boundaries, stealing too-expensive ginger root from the big grocery store...

the other piece of this, for me, is about impact, both on physical and metaphysical planes. artists are necessary in a society because they reimagine worlds and make space for growth. not growth in gain, but growth deeper. and i think our biggest challenge over the next fifty years is going to be figuring out how we all can reduce our impact on the earth and the water and the atmosphere. how to tread more lightly and treat each other gently, but also how to dismantle wasteful frivolousness and the endless mass of goods and garbage that has been growing since the industrial revolution and the implementation of mass production.

of course it's not really about us on an individual scale, but even in my practice i think about this all the time. i think wastefulness in art is something a lot of people turn their eyes away from. i have a lot of frustration with, for example, the larger photo-book community because yes, it's so incredible to hold work from someone else in your hands, but shoving another massive coffee table book on my shelf is no different to me than the idea of someone collecting, like, special occasion dishware. it’s exclusive, holds weight, takes up space, uses resources to exist, and is made with what intention? to gain "value" over time? am i supposed to assign an emotional weight to this thing? what about when i die? will this thing then be passed down to someone who may not want the burden placed upon them? i really like zines and paperbacks…i’m also currently laughing at myself, because books are amazing and i love them. but i guess it's not just about books. it's about how we assign value, about waste and voice and power.

i try to own a very small amount of things, and when my time with them ends, i try to pass them along in thoughtful ways. i do like old things, though... things that last a very long time. holding my great-grandfather’s Leica in my hands feels transpirational. that's an item that does NOT feel like a burden to me. and i guess what i'm saying is, well, i believe in not burdening others and not burdening the earth. i believe in trying.

____

Kelsey Sucena (they/them) is a trans*/nonbinary photographer, writer, and park ranger currently residing on Long Island. Their work rests at the intersection of photography and text, often within the bodies of performative slideshows and photo-text-books. It is centered broadly upon the United States as a site for anti-capitalist, queer and critical reflection. Kelsey is a recent MFA graduate from Image Text Ithaca (2020), a former work scholar at Aperture Foundation, and a freelance writer with contributions to Float Photo Magazine, Rocket Science, and 10x10 Photobooks.

Marissa Iamartino uses photography, writing, and an exploratory practice to examine a world in perpetual flux. Her work explores Luck, light, and relationships -- existing as both anecdotal and subversively referential to the history of photography. Marissa is a current MFA Candidate at Image Text Ithaca and holds a BFA from the Massachusetts College of Art and Design. She finds work as a freelance writer and maker, and finds joy in excessive sun and movement

Kelsey Sucena (they/them) is a trans*/nonbinary photographer, writer, and park ranger currently residing on Long Island. Their work rests at the intersection of photography and text, often within the bodies of performative slideshows and photo-text-books. It is centered broadly upon the United States as a site for anti-capitalist, queer and critical reflection. Kelsey is a recent MFA graduate from Image Text Ithaca (2020), a former work scholar at Aperture Foundation, and a freelance writer with contributions to Float Photo Magazine, Rocket Science, and 10x10 Photobooks.

Marissa Iamartino uses photography, writing, and an exploratory practice to examine a world in perpetual flux. Her work explores Luck, light, and relationships -- existing as both anecdotal and subversively referential to the history of photography. Marissa is a current MFA Candidate at Image Text Ithaca and holds a BFA from the Massachusetts College of Art and Design. She finds work as a freelance writer and maker, and finds joy in excessive sun and movement